Last year at CES, UniZ introduced the Slash, a desktop resin printer. It’s fast, it’s capable, and it’s shipping now, but there was something else in the UniZ booth that had a much bigger wow factor.

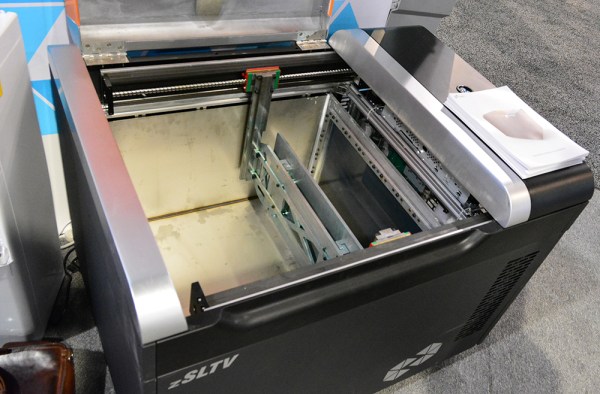

The UniZ zSLTV is a gigantic box, a little more than one meter wide, and a little less than one meter tall and deep. Open the lid, and you see a gigantic resin printer turned on its side. The idea here is to fill a gigantic tank with resin, (the build volume is 521 x 293 x 600 mm) and use it as a fairly standard UV LED / LCD resin printer. The only real difference between this machine and any other resin printer is that the part is always submerged in resin.

It’s something we’ve never seen before, and it will be available ‘soon’. The price for this huge machine is in the ballpark of $10,000.