The first step to reducing the energy consumption of your home is figuring out how much you actually use in the first place. After all, you need a baseline to compare against when you start making changes. But fiddling around with high voltage is something a lot of hackers will go out of their way to avoid. Luckily, as [Xavier Decuyper] explains, you can build a very robust DIY energy monitoring system without having to modify your AC wiring.

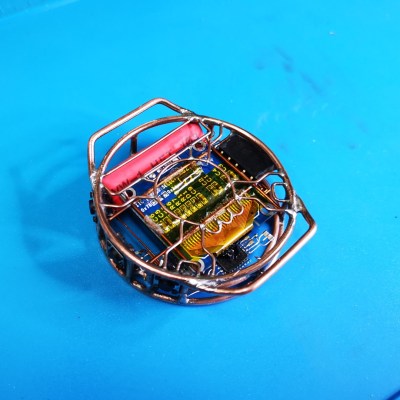

In the video after the break, [Xavier] goes over the theory of how it all works, but the short version is that you just need to use a Current Transformer (CT) sensor. These little devices clamp over an AC wire and detect how much current is passing through it via induction. In his case, he used a YHDC SCT-013-030 sensor that can measure up to 30 amps and costs about $12 USD. It outputs a voltage between 0 and 1 volts, which makes it extremely easy to read using the ADC of your favorite microcontroller.

In the video after the break, [Xavier] goes over the theory of how it all works, but the short version is that you just need to use a Current Transformer (CT) sensor. These little devices clamp over an AC wire and detect how much current is passing through it via induction. In his case, he used a YHDC SCT-013-030 sensor that can measure up to 30 amps and costs about $12 USD. It outputs a voltage between 0 and 1 volts, which makes it extremely easy to read using the ADC of your favorite microcontroller.

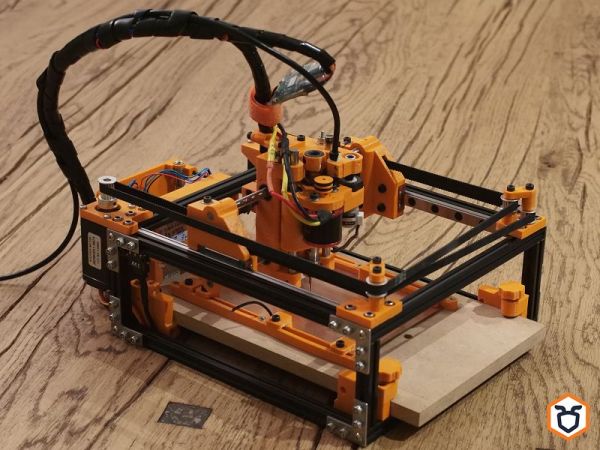

Once you’ve got the CT sensor connected to your microcontroller, the rest really just depends on how far you want to take the software side of things. You could just log the current consumption to a plain text file if that’s your style, but [Xavier] wanted to challenge himself to develop a energy monitoring system that rivaled commercial offerings so he took the data and ran with it.

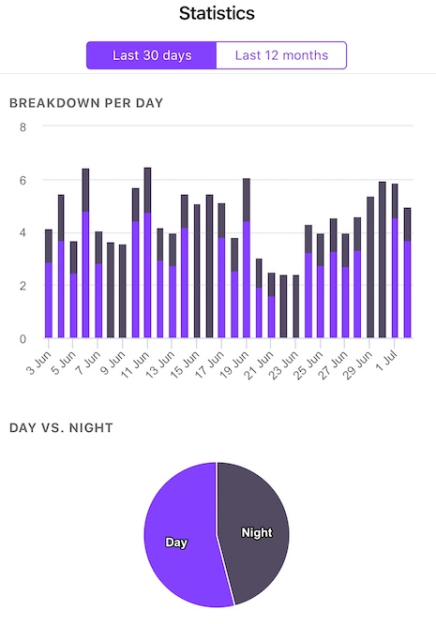

A good chunk of his write-up explains how the used Amazon Web Services (AWS) to process and ultimately display all the data he collects with his ESP32 energy monitor. Every 30 seconds, the hardware reports the current consumption to AWS through MQTT. The readings are stored in a database, and [Xavier] uses GraphQL and Dygraphs to generate visualizations. He even used Ionic to develop a cross-platform mobile application so he can fawn over his professional looking charts and graphs on the go.

We’ve already seen how carefully monitoring energy consumption can uncover some surprising trends, so if you want to go green and don’t have an optically coupled electricity meter, the CT sensor method might be just what you need.

Continue reading “Building A Safe ESP32 Home Energy Monitor”