The ancient question of whether or not it’s possible to construct a circle with the same area as a given square using only a drawing compass and straightedge was finally answered in 1882, where it was proved that pi is a transcendental number, meaning it cannot be accurately represented in a compass-and-straightedge system. This inability to accurately represent pi is just one of the ways in which these systems resemble a computer, a similarity that [0x0mer] explored in CasNum.

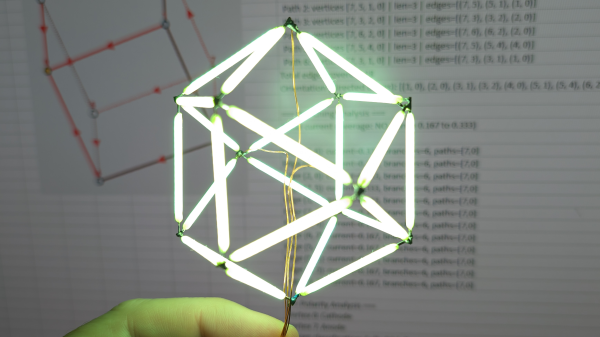

The core of the program represents operations with a drawing compass and unmarked straightedge. There are only a few operations that can be used for calculation: constructing a line through two points, constructing a circle centered at one point and intersecting another point, and constructing the intersection(s) of two lines, a line and a circle, or two circles. An optional viewer visualizes these operations. Another class builds on top of this basic environment to perform arithmetic and logical operations, representing numbers as points in the Cartesian plane. To add two numbers, for example, it constructs the midpoint between them, then doubles the distance from the origin.

There are some examples available, including the RSA algorithm. [0x0mer] also altered a Game Boy emulator to implement the ALU instructions using compass and straightedge operations. In testing, it took about fifteen minutes to boot, and runs at a “totally almost playable” speed, near one FPS. This is after extensive caching has been applied to minimize computation time; the performance here is impressive, but in a more qualitative than quantitative sense.

Being virtual, this system is discrete, but a physical compass and straightedge form a simple analog computer capable of dealing with continuous values.