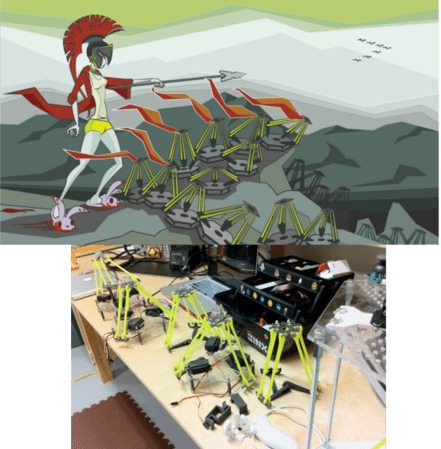

[Sarah Petkus] has a simple dream. She wants to build and command her own delta robot army. It all began with an illustration she drew of a woman hovering over a field of flowers. The flowers in this case had incandescent light bulbs as blooms. [Sarah] decided to create her image in the real world as an interactive art installation. Her first attempts at moving light flowers were based on a pulley system, which was unreliable and not exactly the graceful movement she imagined. Eventually [Sarah] discovered inverted delta robots. She changed her flower design to a delta, and began building her own delta robots out of parts she had around the house.

A chance meeting with the folks at SYN Shop hackerspace in Las Vegas, NV kicked the project into high gear. [Sarah] switched from using R/C ball links as joints to a simple ball bearing joint. She created her entire design in CAD software and printed it on the hackerspace’s 3d printer. She now has six working prototypes. The robots are all controlled via I2C by an Arduino compatible Nymph board. Six robots doesn’t exactly constitute an army, so [Sarah] had to find a new way to fund her project. She’s currently setting up a project for Kickstarter. [Sarah] will be selling kits for her robots, with the proceeds going toward the realization of her dream of a field of robotic light bulb flowers – Assuming the deltas don’t become sentient and try to take over the world first. [Sarah] posts progress updates to her blog, and has a dedicated site (which we featured on Sunday as part of a Links post) for information about her upcoming Kickstarter campaign.