Self-driving cars are, apparently, the next big thing. This thought is predicated on advancements in machine vision and cheaper, better sensors. For the machine vision part of the equation, Nvidia, Intel, and Google are putting out some interesting bits of hardware. The sensors, though? We’re going to need LIDAR, better distance sensors, more capable CAN bus dongles, and the equipment to tie it all together.

This is the cheapest LIDAR we’ve ever seen. The RPLIDAR is a new product from Seeed Studios, and it’s an affordable LIDAR for everyone. $400 USD gets you one module, and bizarrely $358 USD gets you two modules. Don’t ask questions — this price point was unheard of a mere five years ago.

Basically, this LIDAR unit is a spinning module connected to a motor via a belt. A laser range finder is hidden in the spinny bits and connected to a UART and USB interface through a slip ring. Mount this LIDAR unit on a robot, apply power, and the spinny bit does its thing at about 400-500 RPM. The tata that comes out includes distance (in millimeters), bearing (in units of degrees), quality of the measurement, and a start flag once every time the head makes a revolution. If you’ve never converted polar to cartesian coordinates, this is a great place to start.

Although self-driving cars and selfie drones are the future, this part is probably unsuitable for any project with sufficient mass or velocity. The scanning range of this LIDAR is only about 6 meters and insufficient for retrofitting a Toyota Camry with artificial intelligence. That said, this is a cheap LIDAR that opens the door to a lot of experimentation ranging from small robots to recreating that one Radiohead video.

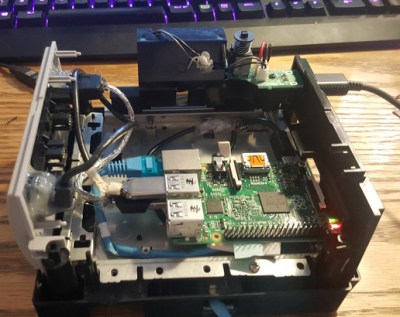

Time marches on, and after a while, the Raspberry Pi 2 was released. By this time, retro emulation was hitting the big time, and [Liam] decided it was time for an upgrade. He disassembled this Nintendo console again, routed new wires and inputs to the original controller ports, and used a Dremel to route a few holes for the HDMI and SD card slot.

Time marches on, and after a while, the Raspberry Pi 2 was released. By this time, retro emulation was hitting the big time, and [Liam] decided it was time for an upgrade. He disassembled this Nintendo console again, routed new wires and inputs to the original controller ports, and used a Dremel to route a few holes for the HDMI and SD card slot.