If you’re building an electric car nowadays, you’re probably looking at taking a normal, gas-powered car and replacing the engine and transmission with an electric motor and batteries. [Gahaar] thought this is a rather dumb idea; all the excesses of an internal combustion-powered car, such as exhaust, cooling, differential, and fuel storage is completely unnecessary. Building a new electric car from the frame up is a vastly more efficient means of having your own electric car. So that’s what he did.

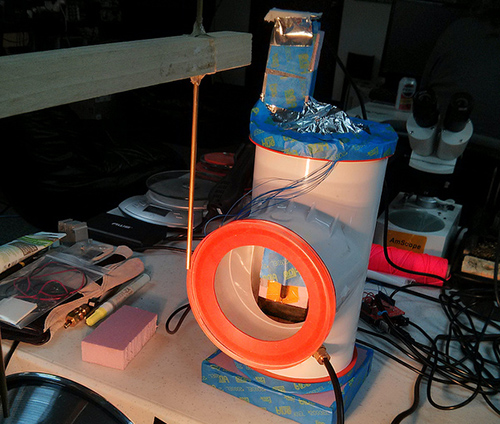

[Gahaar] build his new chassis around a single box made of 3mm aluminum sheet. Attached to this box are two AC induction motors at the rear of the car, negating the need for a differential, with 45 lithium cells stuffed into the middle of the box. There’s no gearbox here, greatly reducing the complexity of the build, and with the batteries providing 145V and 100Ah, this simple car has more than enough power for a lot of fun.

The suspension and steering were taken from a wrecked car, in this case a Mazda MX5, or Miata for those of us in North America. The Miata suspension easily unbolts from the frame of the wrecked car, and with just a little bit of welding can easily be attached to the new electric chassis.

Even though [Gahaar]’s car is basically just a bit of aluminum, motors, suspension, and batteries, he’s getting some awesome performance out of it; he estimates a top speed of 100mph with about 60 miles per charge. It’s an awesome way to get around the farm, and with a custom fiberglass body, we can easily see this being one of the coolest electric vehicles ever made.