When working on a project, plenty of us will reach for an Atmel microcontroller because of the widespread prevalence of the Arduino platform. A few hackers would opt for a bit more modern part like an ESP32. But these Arduino-compatible platforms are far from the only microcontrollers available. The flash-based PIC family of microcontrollers is another popular choice. Since they aren’t quite as beginner or user-friendly, setting up a programmer for them is not as straightforward. [Tahmid] needed to program some old PIC microcontrollers and found the Pi Pico to be an ideal programmer.

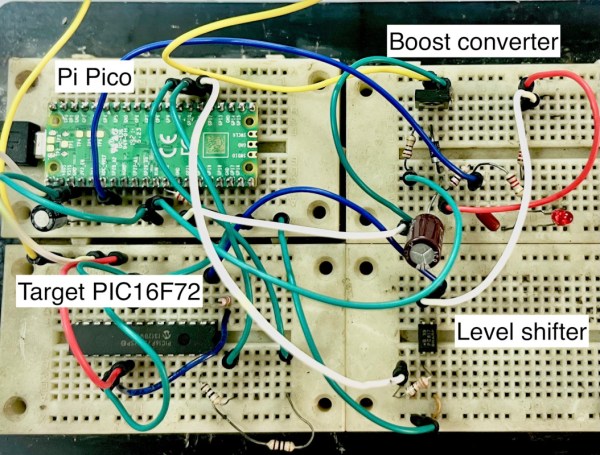

The reason for reaching for the Pico in the first place was that [Tahmid] had rediscovered these decade-old microcontrollers in a parts bin but couldn’t find the original programmer. Thanks to advances in technology in the last ten years, including the advent of micropython, the Pico turned out to be the ideal programmer. Micropython also enables a fairly simple drag-and-drop way of sending the .hex file to the PIC, so the only thing the software has to do is detect the PIC, erase it, and flash the .hex file. The only physical limitation is that the voltages needed for the PIC are much higher than the Pico can offer, but this problem is easily solved with a boost converter (controlled by the Pico) and a level shifter.

[Tahmid] notes that there’s plenty of room for speed and performance optimization, since this project optimized development time instead. He also notes that since the software side is relatively simple, it could be used for other microcontrollers as well. To this end, he made the code available on his GitHub page. Even if you’re more familiar with the Arduino platform, though, there’s more than one way to program a microcontroller like this project which uses the Scratch language to program an ESP32.