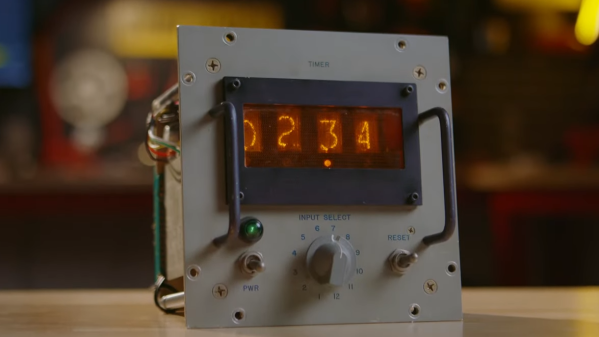

Sometimes you find something that looks really cool but doesn’t work, but that’s an opportunity to give it a new life. That was the case when [Davis DeWitt] got his hands on a weird Soviet-era box with four original Nixie tubes inside. He tears the unit down, shows off the engineering that went into it and explains what it took to give the unit a new life as a clock.

A lot can happen over decades of neglect. That was clear when [Davis] discovered every single bolt had seized in place and had to be carefully drilled out. But Nixie tubes don’t really go bad, so he was hopeful that the process would pay off.

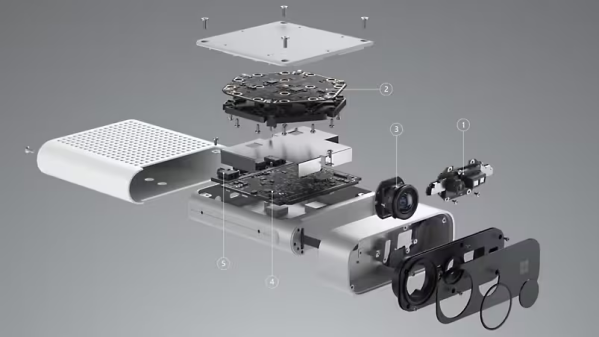

The unit is a modular display of some kind, clearly meant to plug into a larger assembly. Inside the unit, each digit is housed in its own modular plug with a single Nixie tube at the front, a small neon bulb for a decimal point, and a bunch of internal electronics. Bringing up the rear is a card edge connector.

Continues after the break…

Continue reading “Turning Soviet Electronics Into A Nixie Tube Clock”