Of digital electronics, a wise man once said that “Every idiot can count to one.” Truer words have rarely been spoken, because at the end of the day, every digital circuit is really just an analog circuit with the interesting bits abstracted away. And to celebrate that way of looking at things, we’re pleased to present this BCD to seven-segment converter that uses no logic chips.

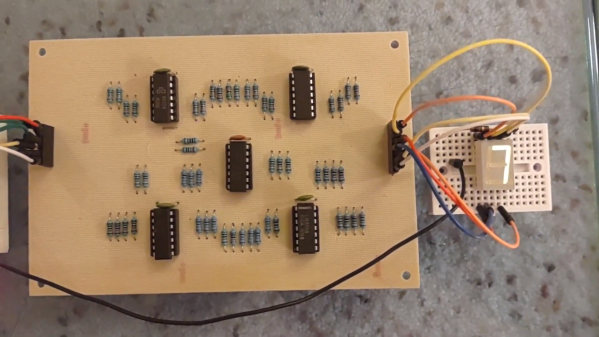

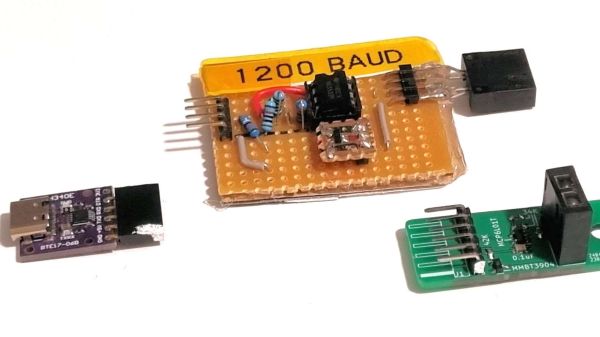

With cheap and easily available chips that perform this exact job, it might seem a little loopy to throw 20 LM324 op-amps at the job. But as [gschmidt958] explains, this is strictly for the challenge, plus it made a nice entry in the recently concluded Op-Amp Challenge contest. His work began in simulation, exploring op-amp versions of the basic logic gates — NAND, AND, OR, and NOT — all of which rely on using the LM324s as comparators. There were real-world curveballs, of course, not least of which was running out of the 10k resistors used for input averaging. Another plot twist was running out of time to order a PCB, which required designing one using MS Paint and etching it at home.

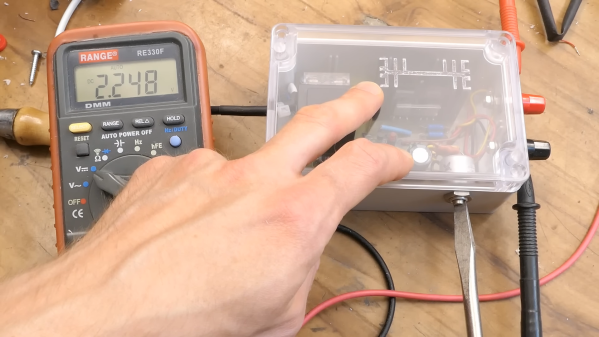

The demo video below shows the circuit at work, taking the BCD output of a 74HC393 counter — clocked by a 555, naturally — and driving a seven-segment LED. It’s honestly a lot of work for such a simple task, but there’s something satisfying about the whole project. We think [Widlar] would be proud.