If you were anywhere near Hackaday over the weekend, you certainly noticed that we launched the tenth annual Hackaday Prize! In celebration of the milestone, we picked from our favorite challenges of years past and came up with four of our favorite, and even one new one just to keep you on your toes. But the first challenge round is running right now, so get your hacking motors turning.

Re-engineering Education

The first challenge this year showcases educational projects, but broadly construed. Hackers tend to learn best by doing. In the Re-engineering Education challenge, we want you to help give others a chance to learn new skills. Whether you’re building a DIY radio kit, a breadboard-it-yourself computer, or even a demonstrator robot arm, if it helps pass on your hard-earned skills, we want you to enter it here.

The first challenge this year showcases educational projects, but broadly construed. Hackers tend to learn best by doing. In the Re-engineering Education challenge, we want you to help give others a chance to learn new skills. Whether you’re building a DIY radio kit, a breadboard-it-yourself computer, or even a demonstrator robot arm, if it helps pass on your hard-earned skills, we want you to enter it here.

It’s fresh on my mind because we were just playing with one this weekend, but [deshipu]’s Fluffbug robot project is a great inspiration for non-traditional education. What better way to discover the intricacies of four-legged walking machine gaits than to have one to play with on your desktop? It’s not going to take over the world, but if you can make it walk, you’ve learned something.

More obviously educational is [Joan Horvath]’s Hacker Calculus, an entry in last year’s Prize. The connections between a function’s height, and the area or volume that it integrates up to can be awfully abstract. Printing out 3D models of the resulting shapes can really help to bring the point home. Or maybe you could really drive home the speed of a comet in its orbit with a physical model? They’ve got you covered, but also ideas for generating your own plastic math toys.

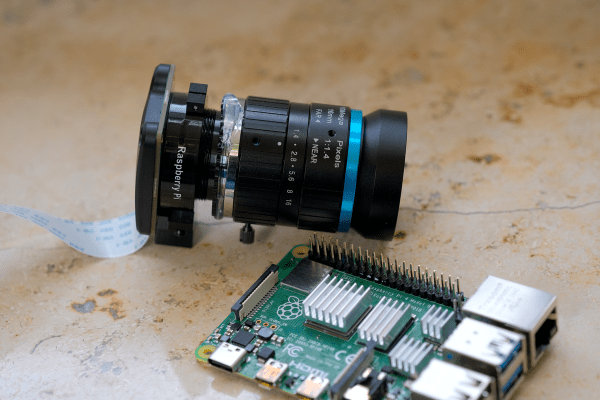

When we think educational computer builds, the amazing reproduction of the WDC-1 “Working Digital Computer” by [Michael Gardi] springs instantly to mind, but perhaps it goes too far down the rabbit hole. Just another rung up on the complexity ladder gets you the Blinking Computer by [Tony Robinson]. Or if you want to figure out how an almost-commercial Z80 computer works from the ground up, consider the Baffa 2.

So what skills do you have that you want to teach other hackers? Can you embody that in a project?

All the Challenges

If you don’t have education in your sights, have a look at the rest of the 2023 Hackaday Prize Challenge rounds. We’re sure you’ll find something you like.

To enter, simply set up a project on Hackaday.io. When the challenge is running, you’ll be able to enter. Full rules over at the 2023 Hackaday Prize landing page.

| Challenge | Date | The Details |

|---|---|---|

| Re-engineering Education | March 25 – April 25 | Educational projects of all stripes welcome. If the goal is to teach, enter it here. |

| Assistive Tech | April 25 – May 30 | The Assistive Tech challenge calls for projects that help people with disabilities to learn, work, move around, and simply live their lives to the fullest. |

| Green Hacks | May 30 – July 4 | Help reduce our impact on the planet. Do more with less, or help clean up the mess. |

| Gearing Up | July 4 – August 8 | Hackers build their own tools. What have you made that makes your making easier? Share it with us. |

| Wildcard | August 8 – September 12 | This is where anything goes. The wildcard challenge lets your projects speak for themselves. |

Continue reading “The 2023 Hackaday Prize Is Ten, First Challenge Is Educational”