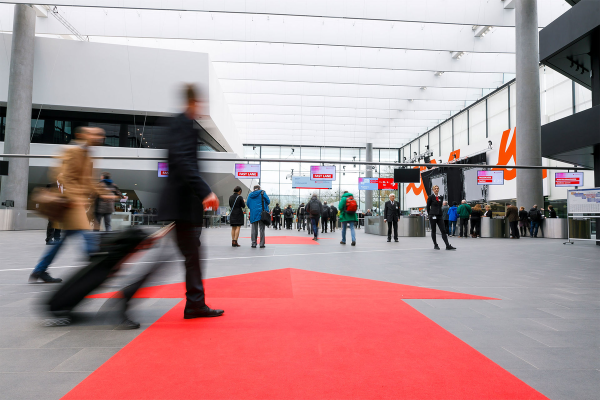

Yesterday I went up to the Embedded World trade fair in Nuremburg, Germany. As a lone hacker, you often feel more than a little out of place when you buy chips in single unit quantities and the people you’re talking to are used to minimum order quantities of a million. But what’s heartening is how, once you ask an interesting question, even some of the suit-wearing types flip into full-on kids who like to explain the fun tech. I struck up conversations with more than a couple VPs of global chip behemoths, and they were cool.

But my heart is still with the smaller players, and the hackers. That’s where the innovation is. I met up with Colin O’Flynn, of Chip Whisperer fame — his company is selling fancier chip-glitching tools, but he still had a refined version of the open source, quick-and-dirty zapper circuit from his Remoticon talk last year. There was a small local company producing virtual buttons that were essentially Pepper’s Ghost illusions floating in mid-air, and the button press was detected by reflective IR. Cool tech, but I forgot the company’s name — sorry!

Less forgettable was Dracula Technologies, a French company making inkjet-printable organic solar cells. While they wouldn’t go into deep details about the actual chemistry of what they’re doing, I could tell that it pained them to not tell me when I asked. Anyway, it’s a cool low-power solar tech that would be awesome if it were more widespread. I think they’re just one of many firms in this area; keep your eyes on organic solar.

When talking with a smaller German FPGA manufacturer, Cologne Chip, about their business, I finally asked about the synthesis flow and was happily surprised to hear that they were dedicated to the fully open-source Yosys toolchain. As far as I know, they’re one of the only firms who have voluntarily submitted their chips’ specs to the effort. Very cool! (And a sign of things to come? You can always hope.)

I met a more than a few Hackaday readers just by randomly stumbling around, which also shows that the hacker spirit is alive in companies big and small. All of the companies have to make demos to attract our attention, but from talking to the people who make them, they have just as much fun building them as you or I would.

And last but not least, I ran into Hackaday regular Chris Gammell and my old boss and good friend Mike Szczys who were there representing the IoT startup Golioth, and trying to fool me into using an RTOS on microcontrollers. (Never say never.) We had an awesome walkaround and a great dinner.

If you ever get the chance to go to a trade show like this, even if you feel like you might be out of your league, I encourage you to attend anyway. You’d be surprised how many cool geeks are hiding in the least likely of places.

[Banner image: Embedded World]