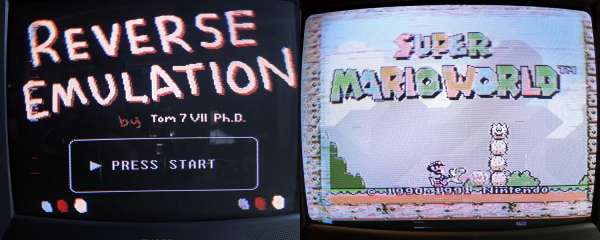

This is a stellar hack, folks. [Tom7] pulled off both full-motion video and running a Super Nintendo game on a regular old Nintendo with one very cute trick. And he gives his presentation of how he did it on the Nintendo itself — Nintendo Power(point)! The “whats” and the “hows” are explained over the course of two videos, also embedded below.

In the first, he shows it all off and gives you the overview. It’s as simple as this: Nintendo systems store 8×8 pixel blocks of graphics for games on their ROM cartridges, and the running program pulls these up and displays them. If you’re not constrained to have these blocks stored in ROM, say if you replaced the cartridge with a Raspberry Pi, you could send your own graphics to be displayed.

He demos a video of a familiar red-haired English soul-pop singer by doing just that — every time through the display loop, the “constant” image block is recalculated by the Raspberry Pi to make a video. And then he ups the ante, emulating an SNES on the Pi, playing a game that could never have been played on an NES in emulation, and sending the graphics block by block back to the Nintendo. Sweet!

The second video talks about how he pulled this off in detail. We especially liked his approach to an epic hack: spend at least a day trying to prove that it’s impossible, and when you’ve eliminated all of the serious show-stoppers, you know that there’s a good chance that it’ll work. Then, get to work. We also learned that there were capacitors that looked identical to resistors used in mid-80s Japan.

These are long videos, and the first one ends with some wild speculation about how a similar human-brain augmentation could take a similar approach, replacing our “memories” with computed data on the fly. (Wait, what?!? But a cool idea, nonetheless.) There’s also another theme running through the first video about humor, but frankly we didn’t get the joke. Or maybe we just don’t know what’s funny. Comments?

None of that matters. A SNES game was played in an NES by pushing modified graphics from a “ROM” cartridge in real-time. And that’s awesome!

If you want more Nintendo-in-Nintendo goodness, check out this NES ROM that’s also a zip file that contains its own source code. If you compile the source, you get the zip file, which if you unzip gives you the source to compile. Right?

Continue reading “Reverse-Emulating NES: Nintendception!” →