Most readers will be familiar with Ethernet networks in some form, in particular the Cat5 cables which may snake around the back of our benches. In a similar vein, we’ll have used power over Ethernet, or PoE, to power devices such as webcams. Buy a PoE router or switch, plug in a cable, and away you go! But what lies behind PoE, and how does it work? [Alan] has written a comprehensive guide, based on experience working with the technology.

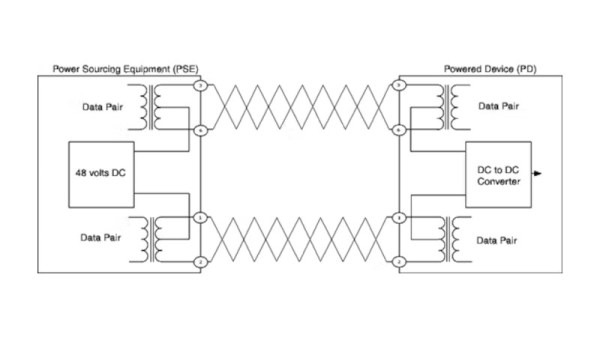

What we get first is a run-down of the various topographies involved. Then [Alan] dives into the way a PoE port polls for a PoE device to be connected, identifies it, and ramps up the voltage. Explaining the various different circuits is particularly valuable. The final part of the show deals with the design of a PoE module, with a small switching power supply to give the required 48 volts.

All in all, this should be required reading for anyone who works with Ethernet, because it’s one of those things too often presented as something of a black box. If you’re thirsty for more, it’s a subject Hackaday have touched on too in the past.