The world of automated farming may be an unglamorous one to those not invested in its attractions, but like the robots themselves that quietly get on in the background with tending crops, those who follow that path spend many seasons refining their designs. The Acorn is a newly-open-sourced robot from Twisted Fields, a Californian research farm, and it provides a fascinating look at the progress of a farming robot design from germination onwards.

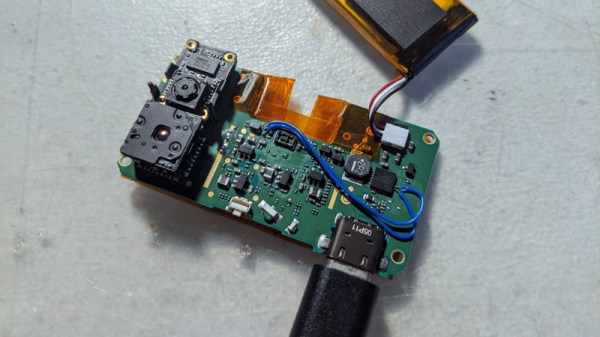

The Acorn is not a CNC gantry for small intensive gardens in the manner of designs such as the Farmbot, instead it’s an autonomous solar-powered rover intended for larger farms which will cruise the fields continuously tending to the plants in its patch. It’s a work in progress, so what we see is the completed rover with the tools and machine vision to follow. It pursues the course of a low-cost lightweight platform, an aluminium chassis surmounted by the solar panel, with mountain bike front fork derived wheels at each corner. It has four wheel drive and four wheel steering, meaning that it can traverse the roughest of farmland. We can see its progress since a 2019 prototype, and while it seems as slow as the seasons themselves to mature, we can see that the final version could be a significantly useful machine on a small farm.

It’s not the first autonomous farming robot we’ve seen over the years, as for example this slightly more robust Australian model. We’re guessing that this is the direction autonomous farming is likely to take, with the more traditional tractor-based machinery projected by some manufacturers taking on repetitive loading and hauling roles.

Continue reading “A New Open-Source Farming Robot Takes Shape”