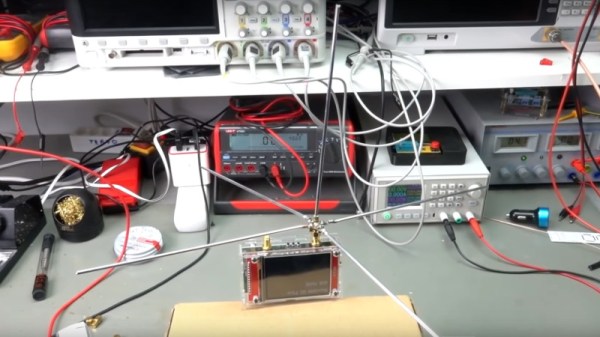

Analogue TV is something that most of us consider to have been consigned to the history books about a decade ago depending on where in the world we are, as stations made the transition to much more power and frequency efficient digital multiplexes. However some of them still cling on for North American viewers, and [Antenna Man] took a trip to Upstate New York in search of some of them before their final switch-off date later this year.

What he reveals can be seen in the video below the break, an odd world of a few relatively low-power analogue TV stations still serving tiny audiences, as well as stations that only exist because their sound carrier can be picked up at the bottom of the FM dial. These stations transmit patterns or static photographs, with their income derived from the sound channel’s position as an FM radio station. While his journey is an entertaining glimpse into snowy-picture nostalgia it does also touch on some other aspects of the aftermath of analogue TV boradcasting. The so-called “FrankenFM” stations sound much quieter, we’re guessing because of the lower sound carrier deviation of the CCIR System M TV spec compared to regular FM radio. And we’re told that there are more stations remaining in Canada, so get out there if you still want to see an analogue picture before they’re gone forever. Where this is being written the switch to DVB was completed in 2013, and it’s still a source of regret that we didn’t stay up to see the final closedown.

Does your country still have an analogue TV service? Tell us in the comments.

Continue reading “The Last Few Analogue TV Stations In North America”