With electric vehicles such as the Tesla or the Leaf being all the rage and joined by fresh competitors seemingly every week, it seems the world is going crazy for the electric motor over their internal combustion engines. There’s another sector to electric traction that rarely hits the headlines though, that of converting existing IC cars to EVs by retrofitting a motor. The engineering involved can be considerable and differs for every car, so we’re interested to see an offering for the classic Mini from the British company Swindon Powertrain that may be the first of many affordable pre-engineered conversion kits for popular models.

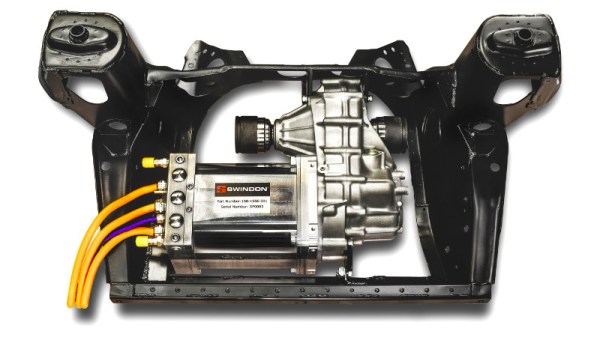

The kit takes their HPD crate EV motor that we covered earlier in the year, and mates it with a Mini front subframe. Brackets and CV joints engineered for the kit to drop straight into the Mini. The differential appears to be offset to the right rather than the central position of the original so we’re curious about the claim of using the Mini’s own driveshafts, but that’s hardly an issue that should tax anyone prepared to take on such a task. They can also supply all the rest of the parts for a turnkey conversion, making for what will probably be one of the most fun-to-drive EVs possible.

The classic Mini is now a sought-after machine long past its days of being dirt-cheap old-wreck motoring for the masses, so the price of the kit should be viewed in the light of a good example now costing more than some new cars. We expect this kit to have most appeal in the professional and semi-professional market rather than the budget end of home conversions, but it’s still noteworthy because it is a likely sign of what is to come. We look forward to pre-engineered subframes becoming a staple of EV conversions at all levels. The same has happened with other popular engine upgrades, and no doubt some conversions featuring them will make their way to the pages of Hackaday.

We like the idea of conversions forming part of the path to EV adoption, as we’ve remarked before.