With nearly sixty exciting entries, the Train All the Things contest, presented in partnership with Digi-Key, has drawn to a close and today we are happy to share news of the winning projects. The challenge at hand was to show off a project using some type of Machine Learning and there were plenty of takes on this theme displayed.

Perhaps the most impressive project is the Intelligent Bat Detector by [Tegwyn☠Twmffat] which claims the “ML on the Edge” award. His project, seen above, seeks not only to detect the presence of bats through the sounds they make during echolocation, but to identify the type of bat as well. Having been through a number of iterations, the bat detector, based on Nvidia Jetson Nano and a Raspberry Pi, can classify several types of bats, and a set of house keys (for a “control”). It’s also been impeccably documented and serves as a great example of how to get into machine learning.

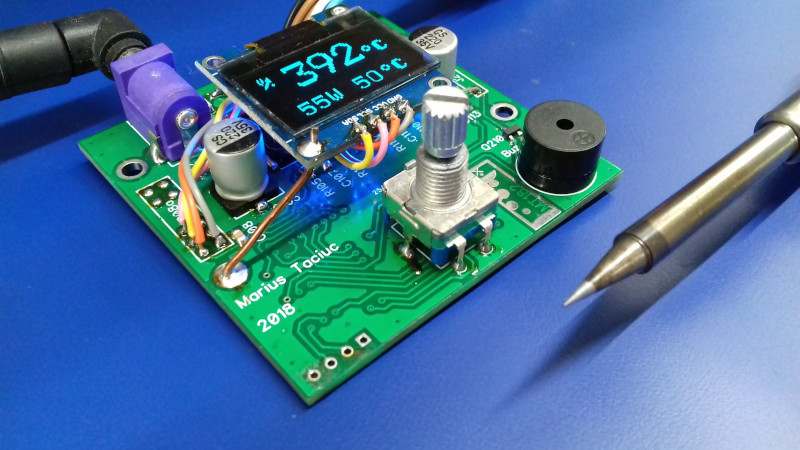

The Soldering LIghtsaber takes the “ML Blinky” award for using machine learning in the microcontroller realm. This clever use of the concept seeks one thing: destroying the wait times for your soldering iron to heat up. It takes time to make temperature readings while the iron heats up, if you can do away with this step it speeds things up greatly. By sampling results of different voltages and heating times, machine learning establishes its own guidelines for how to pour electricity into the heating element without checking for feedback, and coming out the other side at the perfect temperature.

Rounding up our final two winners, the AI Powered Bull**** Detector claims the “ML on the Gateway” award, and

Hacking Wearables for Mental Health and More which won in the “ML on the Cloud” category.

The idea behind our illuminated poop emoji project is to detect human speech and make a judgement on whether the comment is valid, or BS. It does this by leveraging a learning set of comments that have previously been identified as BS and making an association with the currently uttered words.

Wearables for mental health is a wonderful project that was previously recognized in the 2018 Hackaday Prize. Economies of scale have made these wearables quite affordable as a way to add a sensor suite to behavior analysis. But of course you need a way to process all of the sensor data, a perfect task for a cloud-based machine learning application.

All four winners received a $100 gift code to Tindie. Don’t forget to check out all of the other interesting projects that were entered in this contest!

Many readers will be familiar with

Many readers will be familiar with