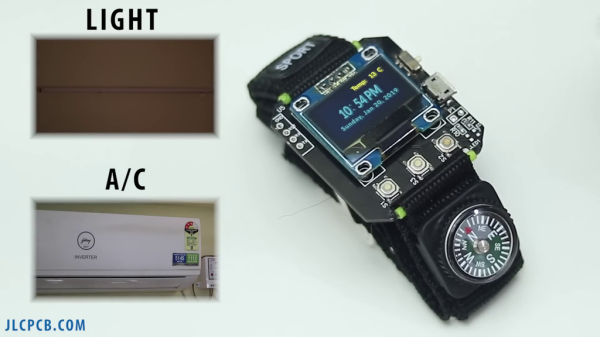

Lamps used to be things built to provide light with specific purpose, whether as reading lamps, desk lamps, or bedside table lamps. Now we just build them for the vibes, as with this minimalist LED lamp from [andrei.erdei].

The build uses a 3D-printed frame printed in opaque grey, with a diffuser element printed in a more translucent white. This is key to allowing the LED to nicely glow through the lamp without ugly distracting hotspots spoiling the effect. The lamp mounts 36 WS2812B LEDs in strip form. These are controlled from an Arduino Nano running the FastLED library for lightweight and easy control of the addressable LEDs. Smooth rainbow animations are made easy by the use of the HSV color space, which is more suitable for this job than the RGB color space you may otherwise be more familiar with.

[andrei.erdei] does a great job of explaining the build, including the assembly, electronics, and code aspects. The latter could serve as a particularly good resource if you’re just starting out on your own builds in the blinky, glowable space. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Minimalist LED Lamp Is Circular Beauty Incarnate”