Do you need a cheap, small computer for a low power computing project? Historically, many of us would reach straight for a Raspberry Pi, even if we didn’t absolutely need the GPIO. But with prices elevated and supplies in the dumps, [Andreas Spiess] decided that it was time to look for alternatives to now-expensive Pi’s which you can see in the video below the break.

Many simply use the Pi for its software ecosystem, its lower power requirements, and diminutive size. [Andreas] has searched eBay, looking for thin PC clients that can be had for as little as $10-15. A few slightly more expensive units were also chosen, and in the video some comparisons are made. How do these thin clients compare to a Pi for power consumption, computing power, and cost? The results may surprise you!

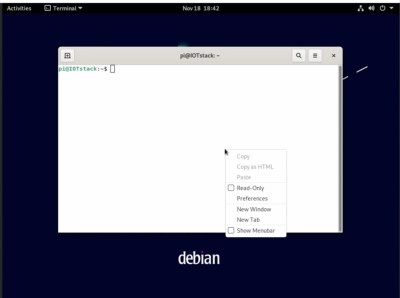

Software is another issue, since many Pi projects rely on Raspbian, a Pi-specific ARM64 Linux distribution. Since Raspbian is based on Debian, [Andreas] chose it as a basis for experimentation. He thoughtfully included such powerful software as Proxmox for virtualization, IOTstack, and Home Assistant, walking the viewer through each step of running Home Assistant on x86-64 hardware and noting the differences between the Linux distributions.

All in all, if you’ve ever considered stepping out of the Pi ecosystem and into general Linux computing, this tutorial will be an excellent starting point. Of course [Andreas] isn’t the first to bark up this tree, and we featured another thin client running Klipper for your 3D printer earlier this month. Have you found your own perfect Pi replacement in these Pi-less times? Let us know in the comments below.