There’s a lot to be said for nice, tidy projects where everything lines up and looks pretty. Seeing straight lines and pleasing proportions speaks to our obsessive-compulsive tendencies, and tends to soothe the mind and calm the spirit. But disorder is not without its charm, and mixing it up a little from time to time, such as with this mixed-media digital clock, can be a good idea.

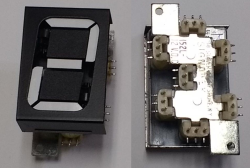

Now, we know what you’re thinking — yet another Nixie clock. True, but that’s only half the story — or more accurately, one-sixth. There’s but a single Nixie in [Fuselage]’s circus-punk themed clock, used for the least significant digit in the hours part of the display. The other digits are displayed with four seven-segment devices — a Numitron, a vacuum fluorescent display, and an LED dot display — plus a real oddball, an old electromechanical display with individual slides for each character and a rear-screen projector. The RTC part of the project is standard Arduino fare, but as you can imagine the power supply needed for such a diversity of displays is pretty complex and has to provide everything from +5 to -270 volts. Each display needs its own driver, too, making this more of a zoo than a circus. The mixed up look just works with the circus theme, too. We’d really like more information on the projector display, though.

Looking for a real statement for your next clock build? Check out the rare as hens’ teeth NIMO tube.

Continue reading “Celebrate Display Diversity For A Circuit Circus Clock”

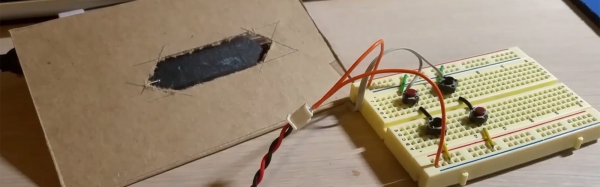

He starts off by building a custom electro-mechanical clock movement, and since he’s planning as he progresses, meccano, breadboard and jumper wires were the way to go. Hot glue helps preserve sanity by keeping all the jumper wires in place. To interface with all of the peripherals in the clock, he decided to use a bank of shift registers driven from a regular Arduino Uno. The more expensive DS3231 RTC module ensures better accuracy compared to the cheaper DS1307 or similar clones. A bank of RGB LEDs acts as an annunciator panel inside the clock to help provide various status indications. The mechanical movement itself went through several iterations to get the time display working with a smooth movement of the hands. Besides displaying time, [David] also added a moon phase indicator dial. A five-rod chime is struck using a stepper motor driven cam and a separate solenoid is used to pull and release three chime hammers simultaneously to generate the loud gong sounds.

He starts off by building a custom electro-mechanical clock movement, and since he’s planning as he progresses, meccano, breadboard and jumper wires were the way to go. Hot glue helps preserve sanity by keeping all the jumper wires in place. To interface with all of the peripherals in the clock, he decided to use a bank of shift registers driven from a regular Arduino Uno. The more expensive DS3231 RTC module ensures better accuracy compared to the cheaper DS1307 or similar clones. A bank of RGB LEDs acts as an annunciator panel inside the clock to help provide various status indications. The mechanical movement itself went through several iterations to get the time display working with a smooth movement of the hands. Besides displaying time, [David] also added a moon phase indicator dial. A five-rod chime is struck using a stepper motor driven cam and a separate solenoid is used to pull and release three chime hammers simultaneously to generate the loud gong sounds.