Texas Instruments is best known to the general public for building obsolete calculators and selling them at extraordinary prices to students, but they also build some interesting (and reasonably-priced) microcontrollers as well. While not as ubiquitous as Atmel and the Arduino platform, they can still be found in plenty of consumer electronics and reprogrammed, and [Aaron] aka [atc1441] demonstrates how to modify them with an ESP32 as an intermediary.

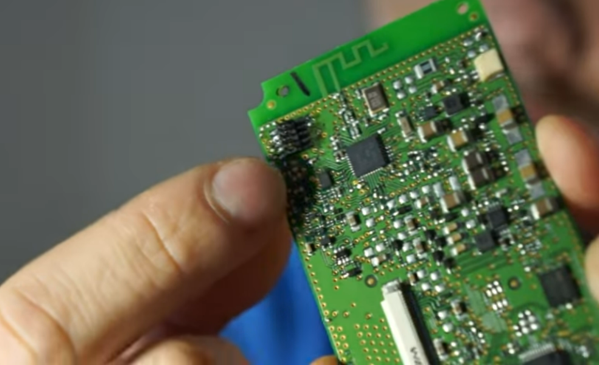

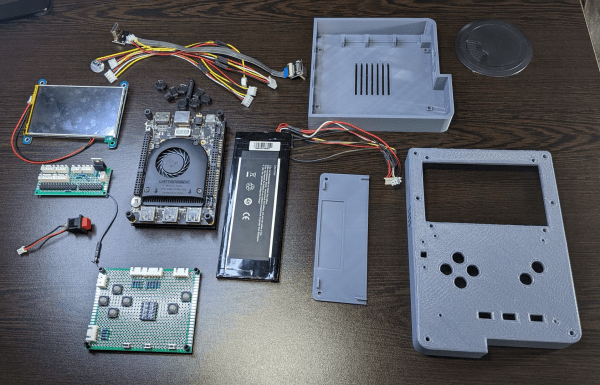

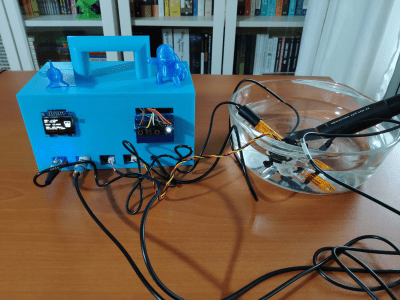

Specifically, the TI chips in this build revolve around the 8051-core microcontrollers, which [Aaron] has found in small e-paper price tags and other RF hardware. He’s using an ESP32 to reprogram the TI chips, and leveraging a web server on the ESP in order to be able to re-flash them over WiFi. Some of the e-paper displays have built-in header pins which makes connecting them to the ESP fairly easy, and once that’s out of the way [Aaron] also provides an entire software library for interacting with these microcontrollers through the browser interface.

Right now the project supports the CC2430, CC2510 and CC1110 variants, but [Aaron] plans to add support for more in the future. It’s a fairly comprehensive build, and much better than buying the proprietary TI programmer, so if you have some of these e-paper displays laying around the barrier to entry has been dramatically lowered. If you don’t have this specific type of display laying around, we’ve seen similar teardowns and repurposing of other e-paper devices in the past as well.