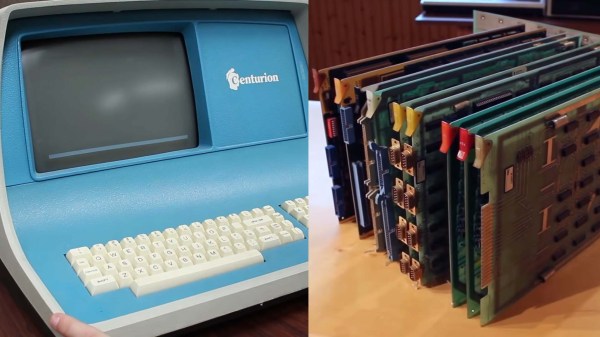

[David Lovett] aka Usagi Electric has spent the last several months dissecting a Centurion minicomputer from 1980. His latest update reveals that the restoration has hit several snags, and bootstrapping this old blue beast is going to be a challenge.

When we last checked in on this project, [David] had built a homebrew ROM reader to backup critical data stored several of the minicomputer’s ROM chips. Since then, the good news is that the Centurion is showing signs of life. Probing the Data Set Ready pin on the default RS232 serial port reveals a stream of data, likely stemming from the ‘CPU6’ board.

Unfortunately, that’s where the good news ends. Adding a terminal to the serial port interrupts this stream of data, and no information appears to be sent or received from any of the three terminals tested. To make matters worse, both of the massive hard drives appeared to have suffered catastrophic head crashes at some point in the 1990s, destroying the Centurion operating system and likely other important data in the process. Soiled air filters were the likely culprits, with evidence showing that yearly maintenance had been overlooked. While at least one of the drives can be repaired with new platters, the original operating system is completely lost.

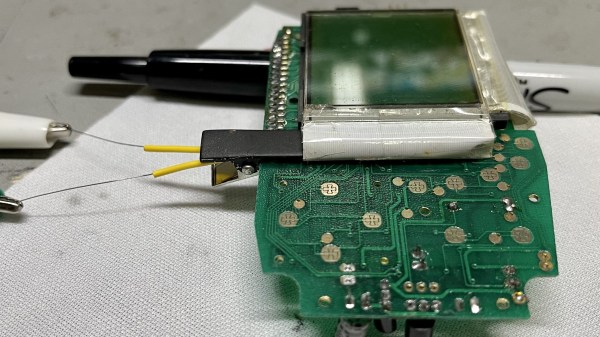

As luck would have it, a previous employee of Centurion was able to provide a wealth of undocumented information that greatly aided in making sense of the minicomputer’s individual components. Incredibly, they were also able to provide a PROM Diagnostic board for the Centurion system. Not only could this board run a barrage of tests, it could also bootstrap the system with TOS (Test Operating System), a bare-bones memory monitor stored on the card’s PROMs. While the diagnostic card itself needs repairs, there’s now the slightest chance that [David] can use TOS as the starting off point for writing new software for the Centurion.

We really can’t wait to see what happens next with this project. We’ve covered some very special vintage computer restorations in the past, such as the cursed Diablo drive from a rare Xerox Alto, not to mention the delicate power-up procedure for an original Apple 1.

Continue reading “Minicomputer Restoration Hanging In The Balance”