Older Apple computers can often be something of a collector’s item, with the oldest fetching an enormously high price in auctions. The ones from the late ’80s and early ’90s don’t sell for quite as much yet, but it’s possible that museums and collectors of the future will one day be clamoring for those as well. For that reason, it’s generally frowned upon to hack or modify original hardware. Luckily, this replica of an Apple Macintosh didn’t harm any original hardware yet still manages to run software on bare metal.

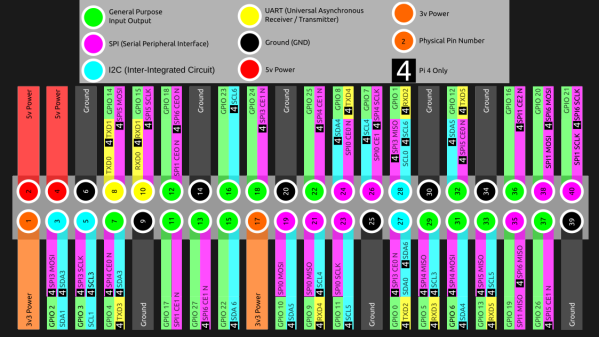

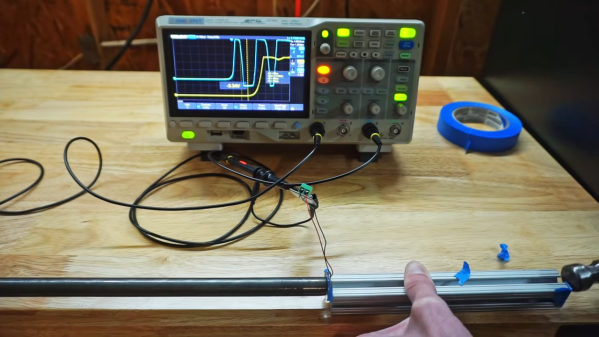

The computer is built around a single-board computer, but this SBC isn’t like the modern ARM machines that have become so ubiquitous. It’s a 133MHz AMD 486 which means that it can run FreeDOS and all of the classic DOS PC games of that era without emulation. In order to run Apple’s legacy operating system, however, it does require the use of the vMac emulator, but the 486 is quite capable of handling the extra layer of abstraction. The computer also sports a real SoundBlaster ISA sound card, uses a microSD card for its hard drive, and uses an 800×600 LCD screen.

As a replica, this computer is remarkably faithful to the original and even though it doesn’t ship with a Motorola 68000 it’s still fun to find retro PC gamers that are able to run their games on original hardware rather than emulation. It reminds us of another retro 486 that is capable of running old games on new hardware without an emulator as well.