While not impossible, replicating the machines and processes of a modern semiconductor fab is a pretty steep climb for the home gamer. Sure, we’ve seen it done, but nanoscale photolithography is a demanding process that discourages the DIYer at every turn. So if you want to make semiconductors at home, it might be best to change the rules a little and give something like this pulsed laser deposition prototyping apparatus a try.

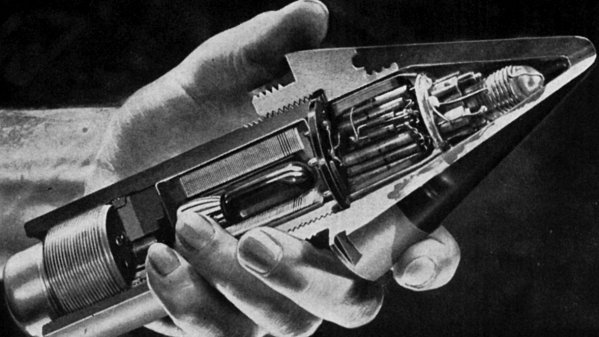

Rather than building up a semiconductor by depositing layers of material onto a silicon substrate and selectively etching features into them with photolithography, [Sebastián Elgueta]’s chips will be made by adding materials in their final shape, with no etching required. The heart of the process is a multi-material pulsed laser deposition chamber, which uses an Nd:YAG laser to ablate one of six materials held on a rotating turret, creating a plasma that can be deposited onto a silicon substrate. Layers can either be a single material or, with the turret rapidly switched between different targets, a mix of multiple materials. The chamber is also equipped with valves for admitting different gases, such as oxygen when insulating layers of metal oxides need to be deposited. To create features, a pattern etched into a continuous web of aluminum foil by a second laser is used as a mask. When a new mask is needed, a fresh area of the foil is rolled into position over the substrate; this keeps the patterns in perfect alignment.

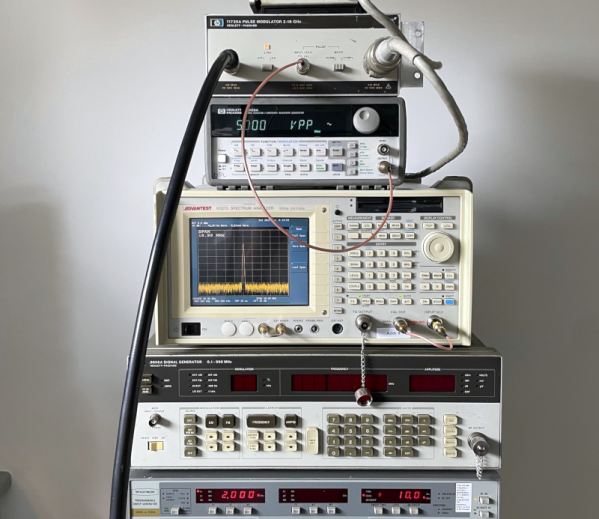

We’ve noticed regular updates on this project, so it’s under active development. [Sebastián]’s most recent improvements to the setup have involved adding electronics inside the chamber, including a resistive heater to warm the substrate before deposition and a quartz crystal microbalance to measure the amount of material being deposited. We’re eager to see what else he comes up with, especially when those first chips roll off the line. Until then, we’ll just have to look back at some of [Sam Zeloof]’s DIY semiconductors.