When you acquired your first oscilloscope, what were the first waveforms you had a look at with it? The calibration output, and maybe your signal generator. Then if you are like me, you probably went hunting round your bench to find a more interesting waveform or two. In my case that led me to a TV tuner and IF strip, and my first glimpse of a video signal.

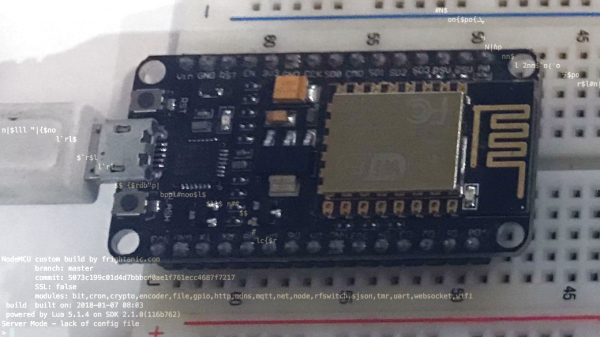

An analogue video signal may be something that is a little less ubiquitous in these days of LCD screens and HDMI connectors, but it remains a fascinating subject and one whose intricacies are still worthwhile knowing. Perhaps your desktop computer no longer drives a composite monitor, but a video signal is still a handy way to add a display to many low-powered microcontroller boards. When you see Arduinos and ESP8266s producing colour composite video on hardware never intended for the purpose you may begin to understand why an in-depth knowledge of a video waveform can be useful to have.

The purpose of a video signal is to both convey the picture information in the form of luminiance and chrominance (light & dark, and colour), and all the information required to keep the display in complete synchronisation with the source. It must do this with accurate and consistent timing, and because it is a technology with roots in the early 20th century all the information it contains must be retrievable with the consumer electronic components of that time.

We’ll now take a look at the waveform and in particular its timing in detail, and try to convey some of its ways. You will be aware that there are different TV systems such as PAL and NTSC which each have their own tightly-defined timings, however for most of this article we will be treating all systems as more-or-less identical because they work in a sufficiently similar manner.