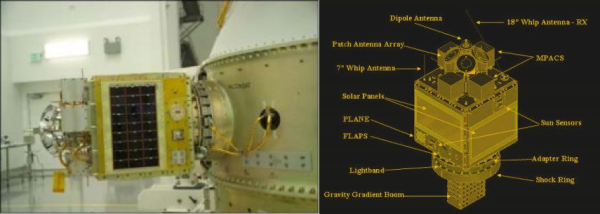

Space may be the final frontier, but that doesn’t mean we all get to explore it. Except, perhaps by radio, as the US Air Force has just demobbed a satellite and handed it over to the public to use. FalconSAT-3 was built and used by students at the US Air Force Academy (USAFA) as part of their training, then launched into orbit in 2007. It’s still going 10 years later, but the USAFA is building and launching more satellites, so they don’t need FalconSAT-3. Rather than trash it, they have turned off the military bits and and are allowing radio amateurs to use it.

Calculus In 20 Minutes

If you went to engineering school, you probably remember going to a lot of calculus classes. You may or may not remember a lot of calculus. If you didn’t go to engineering school, you will find that there’s an upper limit to how much electronics theory you can learn before you have to learn calculus. Now imagine Khan Academy, run by an auctioneer and done without computers. Well, you don’t have to imagine it. Thinkwell has two videos that purport to teach you calculus in twenty minutes (YouTube, embedded below).

We are going to be honest. If you need a refresher, these videos might be useful. If you have no idea how to do calculus, maybe these are going to whiz by a little fast. However, either way, the videos have some humor value both from the FedEx commercial-style delivery to the non-computerized graphics (not to mention the glass-breaking sound effects). Of course, the video is about ten years old, but that’s part of its charm.

Pitmaster BBQ Dashboard Monitors Your Meat And Veggies

Barbecue is all about temperature, about making sure that whatever is on the grill reaches the right temperature. At least, that is the part that makes sure you don’t poison people, because your food should get hot enough to kill any bacteria. [Chris Aquino] decided to take this a step further than simply sticking a thermometer into a hunk of meat by creating Pitmaster. This combination of hardware and software monitors the temperature of multiple chunks of food and alerts you when each is ready, all through a web interface.

Continue reading “Pitmaster BBQ Dashboard Monitors Your Meat And Veggies”

Part Soldering Iron, Part Hand-Held Oscilloscope

If you are in the market for a temperature controlled soldering iron, an attractive choice of the moment is the TS-100 iron available by mail-order from China. This is an all-in-one iron with a digital temperature controller built into its handle, featuring a tiny OLED display. It’s lightweight, reasonable quality, and all its design and software are available and billed as open source (Though when we reviewed it we couldn’t find an open source licence accompanying the code.) This combination has resulted in it becoming a popular choice, and quite a few software hacks have appeared for it.

The latest one to come our way is probably best described as coming from the interface between genius and insanity without meaning to disparage the impressive achievement of its author. [Befinitiv] has implemented a working oscilloscope on a TS-100, that uses the soldering iron tip as a probe and the OLED as a display. It requires a small modification to the hardware to bring the iron contact into an ADC pin on the microcontroller, and there is currently no input protection on it so the iron could easily be fried, but it works.

It is strongly suggested in the write-up that this isn’t a production-ready piece of work and that you shouldn’t put it on your iron. At least, not without that input protection and maybe a resistive divider. But for all that it’s still an impressive piece of work, a working soldering iron that becomes a ‘scope on a menu selection. Take a look at the ‘scope-iron in action, we’ve posted a video below the break.

Continue reading “Part Soldering Iron, Part Hand-Held Oscilloscope”

Hackaday Prize Entry: Visioneer Sensor HUD

Only about two percent of the blind or visually impaired work with guide animals and assistive canes have their own limitations. There are wearable devices out there that take sensor data and turn the world into something a visually impaired person can understand, but these are expensive. The Visioneer is a wearable device that was intended as a sensor package for the benefit of visually impaired persons. The key feature: it’s really inexpensive.

The Visioneer consists of a pair of sunglasses, two cameras, sensors, a Pi Zero, and bone conduction transducers for audio and vibration feedback. The Pi listens to a 3-axis accelerometer and gyroscope, a laser proximity sensor for obstacle detection within 6.5ft, and a pair of NOIR cameras. This data is processed by neural nets and OpenCV, giving the wearer motion detection and object recognition. A 2200mA battery powers it all.

When the accelerometer determines that the person is walking, the software switches into obstacle avoidance mode. However, if the wearer is standing still, the Visioneer assumes you’re looking to interact with nearby objects, leveraging object recognition software and haptic/audio cues to relay the information. It’s a great device, and unlike most commercial versions of ‘glasses-based object detection’ devices, the BOM cost on this project is only about $100. Even if you double or triple that (as you should), that’s still almost an order of magnitude of cost reduction.

Retrotechtacular: An Oceanographic Data Station Buoy For The 1960s

When we watch a TV weather report such as the ones that plaster our screens during hurricane season, it is easy to forget the scale of the achievement they represent in terms of data collection and interpretation. Huge amounts of data from a diverse array of sources feed weather models running on some of our most powerful computers, and though they don’t always forecast with complete accuracy we have become used to their getting it right often enough to be trustworthy.

It is also easy to forget that such advanced technology and the vast array of data behind it are relatively recent developments. In the middle of the twentieth century the bulk of meteorological data came from hand-recorded human observations, and meteorologists were dispatched to far-flung corners of the globe to record them. There were still significant areas of meteorological science that were closed books, and through the 1957 International Geophysical Year there was a concerted worldwide effort to close that gap.

We take for granted that many environmental readings are now taken automatically, and indeed most of us could produce an automated suite of meteorological instruments relatively easily using a microcontroller and a few sensors. In the International Geophysical Year era though this technology was still very much in its infancy, and the film below the break details the development through the early 1960s of one of the first automated remote ocean sensor buoys.

Perhaps our last sentence conjures up a vision of something small enough to hold, from all those National Geographic images of intrepid oilskin-clad scientists launching them from the decks of research vessels. But the technology of the early 1960s required something a little more substantial, so the buoy in question is a (using the units of the day) 100 ton circular platform more in the scale of a medium-sized boat. Above deck it was dominated by an HF (shortwave) discone antenna and its atmospheric instrument package. Below deck (aside from its electronic payload) it had a propane-powered internal combustion engine and generator to periodically charge its batteries. In use it would be anchored to the sea floor, and it was designed to operate even in the roughest of maritime conditions.

The film introduces the project, then looks at the design of a hull suitable for the extreme conditions like a hurricane. We see the first prototype being installed off the Florida coast in late 1964, and follow its progress through Hurricane Betsy in 1965. The mobile monitoring station in a converted passenger bus is shown in the heart of the foul weather, receiving constant telemetry from the buoy through 40 foot waves and 110 mph gusts of wind.

We are then shown the 1967 second prototype intended to be moored in the Pacific, this time equipped with a computerised data logging system. A DEC PDP-8 receives the data mounted in the bus, and are told that this buoy can store 24 hours at a stretch for transmission in one go. Top marks to the film production team for use of the word “data” in the plural.

Finally we’re told how a future network of the buoys for presumably the late 1960s and early 1970s could be served by a chain of receiving stations for near-complete coverage of the major oceans. At the height of the Cold War this aspect of the project would have been extremely important, as up-to-the-minute meteorological readings would have had considerable military value.

The film makes an engaging look at a technology few of us will ever come directly into contact with but the benefits of which we will all feel every time we see a TV weather forecast.

Continue reading “Retrotechtacular: An Oceanographic Data Station Buoy For The 1960s”

Classic British Phone Gets A Google Makeover

It may seem like an odd concept to younger readers, but there was once a time when people rented their phones rather than buying them outright. Accordingly, these phones were built like tanks, and seeing one of these sturdy classics of midcentury modern design can be a trip down memory lane for some of us. So retrofitting a retro phone with a Raspberry Pi and Google’s AIY seems like a natural project to tackle for nostalgia’s sake.

The phone that [Alasdair Allan] decided to hack was the iconic British desk telephone, the GPO-746, or at least a modern interpretation of the default rental phone from the late 60s through the 70s. But the phone’s looks were more important than its guts, which were stripped away to make room for the Raspberry Pi and Google AIY hat. [Alasdair] originally thought he’d interface the Pi to the rotary dial through DIOs, until he discovered the odd optical interface of the dialer — a mask rotates over a ring of photoresistors, one for each digit, exposing only one to light from an LED illuminated by a microswitch on the finger stop. The digital interface brings up the Google voice assistant, along with some realistic retro phone line sounds. It’s a work in progress, but you can see where [Alasdair] is in the video below.

If stuffing a Google Pi into a retro appliance sounds familiar, it might be this vintage intercom rebuild you have in mind, which [Alasdair] cites as inspiration for his build.

Continue reading “Classic British Phone Gets A Google Makeover”