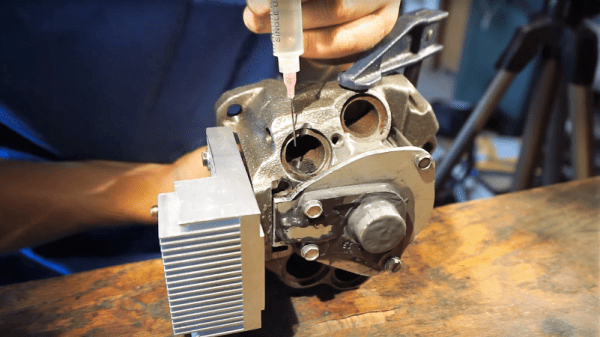

Ben Krasnow is a consummate prototyper. He’s built a machine that makes the perfect chocolate chip cookie, he has a ruby laser, and he produces his own liquid nitrogen in-house because simply filling up a dewar is too easy. If you need a prototype, Ben is the guy to talk to.

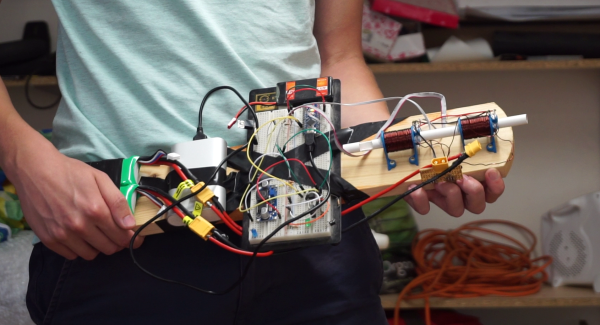

Ben gave a talk at last year’s Hackaday Superconference on prototyping quickly and verifying technical hypotheses. The philosophy can be summed up simply as, ‘Build First, and Ask Questions Later’. This philosophy served him well when he wanted to see if backscatter x-ray machines were actually more effective than metal detectors at TSA checkpoints. The usual bean-counter protocol for answering this question would be to find an x-ray expert, wait weeks, pay tens of thousands of dollars, and eventually get an answer. Ben simply built his own backscatter x-ray machine from parts sourced on eBay.

After the talk, we asked Ben about the limits of this philosophy of building first and asking questions later. With the physical and mental toolset Ben has, it’s actually easy to build something that can get in the ballpark of answering a question. The problem comes when Ben needs to prove something won’t work.

Answering this question is all a matter of mindset. In Ben’s view, if a prototype works, a hypothesis is verified. Even if it’s a complete accident, he’s totally okay with the results. Some of his other colleagues have an opposite mindset — if a quick and dirty prototype doesn’t work, a research hypothesis is verified.

This rapid-proof-of-concept mindset is something we see a lot in the Hackaday audience, and we know there are some of you out there who have a mind and garage that is at least as impressive as Ben’s. We’ve extended the Call for Proposals for the 2017 Hackaday Superconference. If you have a story about rapid prototyping or just making the perfect chocolate chip cookie with robots, we want to hear about it. Tickets are still available for the Superconference in Pasadena, California on November 11th and 12th.