Potatoes deserve to roam the earth, so [Marek Baczynski] created the first self-driving potato, ushering in a new era of potato rights. Potato batteries have been around forever. Anyone who’s played Portal 2 knows that with a copper and zinc electrode, you can get a bit of current out of a potato. Tubers have been powering clocks for decades in science classrooms around the world. It’s time for something — revolutionary.

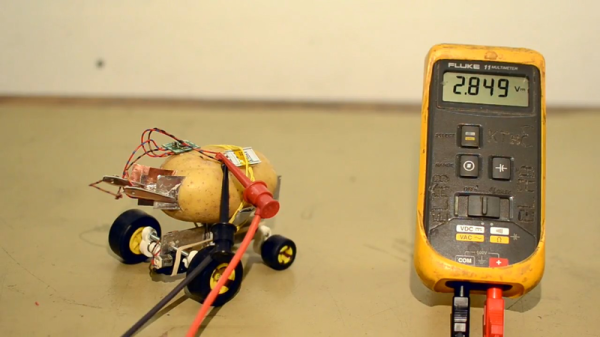

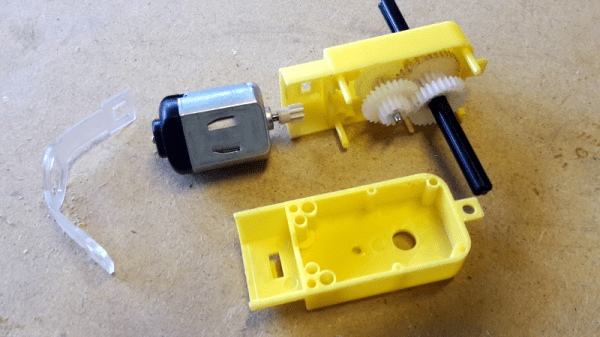

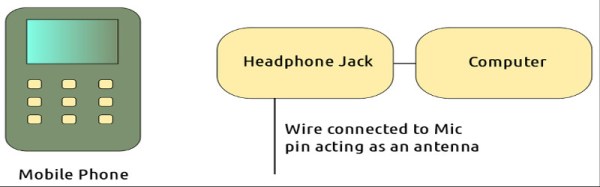

[Marek] knew that powering a timepiece wasn’t enough for his potato, so he picked up a Texas Instruments BQ25504 boost converter energy harvesting chip. A potato can output around 0.4 V at 0.6 mA. The 25504 uses this power to slowly charge a capacitor. Every fifteen minutes or so, enough energy is stored to power a motor for a short time. [Marek] built a car for his potato — or more fittingly, he built his potato into a car.

The starch-powered capacitor moves the potato car about 8 cm per cycle. Over the course of a day, the potato can travel around 7.5 meters. Not very far, but hey, that’s further than the average potato travels on its own power. Of course, any traveling potato needs a name, so [Marek] dubbed his new pet “Pontus”. Check out the video after the break to see the ultimate fate of poor Pontus.

Now that potatoes are mobile, we’re going to need a potato detection system. Humanity’s only hope is to fight fire with fire – break out the potato cannons!