If you head down to your local electronics supply shop (the Internet), you can pick up a quality true-RMS multimeter for about $100 that will do almost everything you will ever need. It won’t be able to view waveforms, though; this is the realm of the oscilloscope. Unlike the multimeter’s realistic price point, however, a decent oscilloscope is easily many hundreds, and often thousands, of dollars. While this is prohibitively expensive for most, the next entry into the Hackaday Prize seeks to bring an inexpensive oscilloscope to the masses.

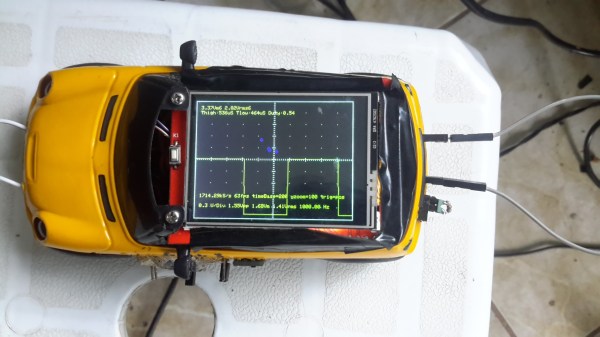

The multiScope is built by [Vítor] and is based on the STM32-O-Scope which is built around a STM32F103C8T6 microcontroller. This particular chip was chosen because of its high clock speed and impressive analog-to-digital resolution, which are two critical specifications for any oscilloscope. This particular scope has an inductance meter built-in as well, which is another feature which your otherwise-capable multimeter probably doesn’t have.

New features continue to get added to this scope by [Vítor]. Most recently he’s added features which support negative voltages and offsets. His particular scope is built inside of a model car, too, but we believe this to be an optional feature.