[The Plutonium Bunny] saw homegrown tin crystals on YouTube and reckoned he could do better—those crystals were flimsy and couldn’t stand up outside of the solution in which they were grown. Having previously tackled copper crystals, he applied the same procedure to tin.

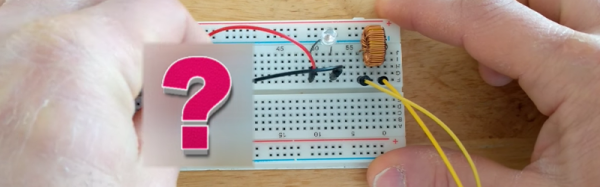

Beginning with a 140 ml baby food jar filled with a solution of tin II chloride, 90 grams per liter, with a small amount of HCl as the electrolyte. A wire at the bottom of the jar was connected to a blob of tin and served as the anode, while the cathode, a loop of tin, stuck down from above. A LM317-based adjustable voltage regulator circuit was used to manage the power running through the solution. Because [The Plutonium Bunny]’s technique involves days or even weeks of very low current, he used six diodes to drop the circuit’s voltage from 1.5 V to 0.25 V, giving him around 13 mA.

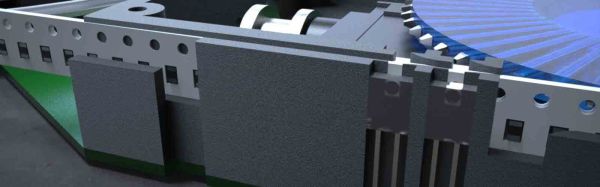

His first attempt seemed to go well and he got some nice shiny crystal faces, but he couldn’t get the current bellow 10 mA without it dropping to the point where no tin was depositing. Rather than reset the experiment he made some changes to the project: he changed the solution by removing 30 ml of the electrolyte and topping it off with water. He also made a gentle agitator out of a DC motor and flattened plastic tube from a pen, powering it with another low-voltage LM317 circuit so he could get the lowest RPM possible.

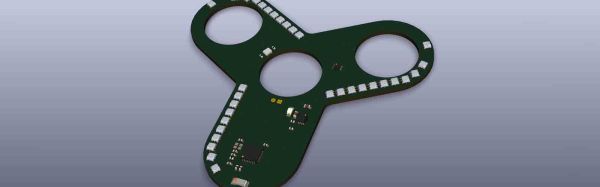

With this new setup [The Plutonium Bunny] began to get much better results, proving his hypothesis that low current with a lower concentration of Sn2+ was the ticket for large crystal growth. We featured his copper crystal experiments last year and he’s clearly making good progress! Video after the break.