A large installed base of powered speakers from a defunct manufacturer and a dwindling supply of working remote controls. Sounds like nightmare fuel for an AV professional – unless you take matters into your own hands and replace the IR remotes with an Arduino and custom software.

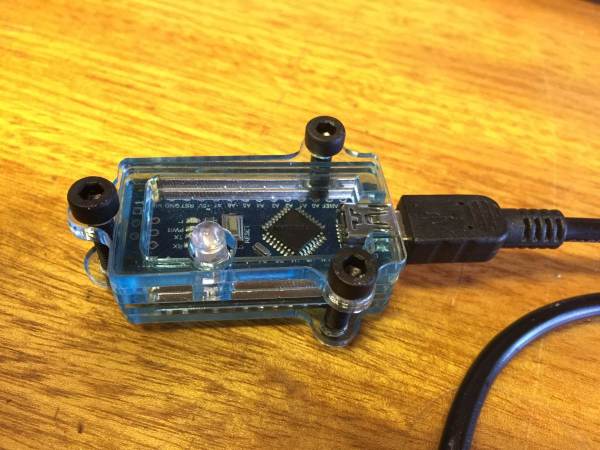

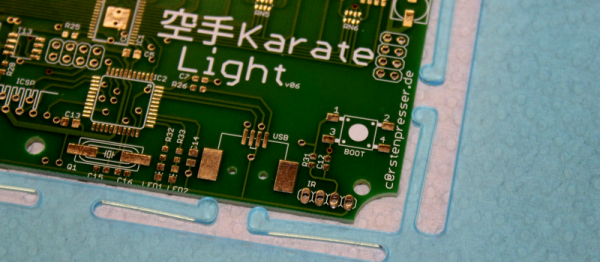

From the sound of it, [Steve]’s crew was working on AV gear for a corporate conference room – powered speakers and an LCD projector. It was the speakers that were giving them trouble, or rather the easily broken or lost remotes. Before the last one gave up the ghost, [Steve] captured the IR codes for each button using an Arduino and the IRRemote library. With codes in hand, it was pretty straightforward to get the Nano to send them with an IR LED. But what makes this project unique is that the custom GUI that controls the Arduino was written in the language that everyone loves to hate, Visual Basic. It’s a dirty little secret that lots of corporate shops still depend on VB, and it’s good to see a little love for the much-maligned language for a change. Plus it got the job done.

Want to dive deeper into IR? Maybe this primer on cloning IR remotes with an Arduino will help. And for another project where VB shines, check out this voice controlled RGB LED lamp.