Hackers and makers aren’t usually too interested in basic round analog clocks. They tend to prefer building altogether more arcane and complicated contraptions to display numbers for the telling of time. [alstroemeria] did just that with this nifty kinetic clock build.

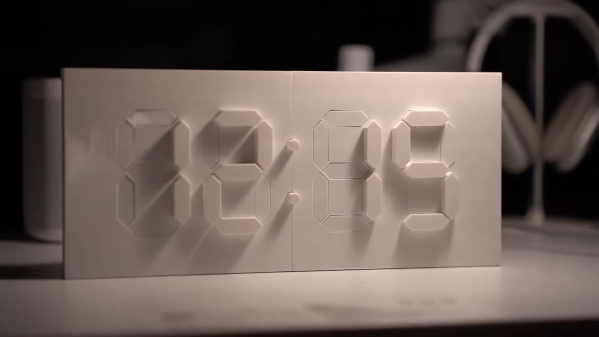

The basic concept of the kinetic clock is to have a flat plate, which individual segments raise out of to create a physical (instead of illuminated) 7-segment display. This is achieved with servos which push the segments in and out using a small rack mechanism. It’s not a sophisticated build; it simply uses 30 servos to handle all the segments needed to tell time. Thus, the Arduino Mega was the perfect tool for the job. With a sensor shield added on, it has an abundance of IO, driving a ton of servos is a cinch. There’s also a DS3231 real time clock to help it keep accurate time.

Incidentally, it’s a hefty thing to print, according to YouTuber [Lukas Deem] who replicated the project. It took around 85 hours to print, and a total of 655 grams of filament – not counting mistakes and trashed parts.

And if you think you’re having deja-vu, you might well be. We’ve seen a take on this exquisite design before. We liked it then, and we like it now.

Overall, it’s a stylish build that looks as good as your 3D printer’s output will allow. A resin printer would be a massive boon in this regard. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Kinetic Clock Is A Clean Modern Way To Tell Time”