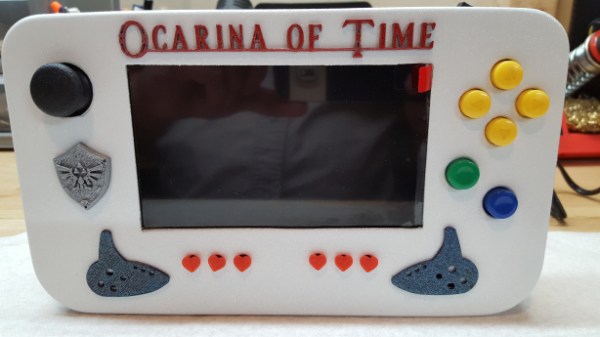

Introducing the SG-N64 — the Single Game Nintendo 64 Portable Console. You can play any game you want, as long as it’s the Ocarina of Time.

You might be wondering, why would you go to the effort of making a totally awesome portable N64 player, and then limit it to but a single game? Well, the answer is actually quite simple.  [Chris] wanted to immortalize his favorite game — the Ocarina of Time. As he puts it, making a SG-N64 “takes the greatness of a timeless classic and preserves it in a body designed solely for the purpose of playing it”.

[Chris] wanted to immortalize his favorite game — the Ocarina of Time. As he puts it, making a SG-N64 “takes the greatness of a timeless classic and preserves it in a body designed solely for the purpose of playing it”.

Inside you’re going to find the motherboard from an original N64, as well as the game cartridge PCB which shed its enclosure and is now hardwired in place. Of course that’s just the start. The real challenge of the build is to add all of the peripherals that are needed: screen, audio, control, and power. He did it, and in a very respectable size considering this was meant to sit in your living room.

Now that is how you show your kids or grand-kids a classic video game. Heck, maybe you can even convince them that’s how all games were sold and played! What’s the fun in being a parent without a bit of trolling?

Continue reading “Handheld Nintendo 64 Only Plays Ocarina Of Time”

Passive cooling is wonderful, and really drops the energy footprint of a data center, albeit a very small one which is being tested. Scaled up, I can think of another big impact: property taxes. Does anyone know what the law says about dropping a pod in the ocean? As far as I can tell, laying undersea cabling is expensive, but once installed there are no landlords holding out their hands for a monthly extraction. Rent aside, taking up space with windowless buildings sucking huge amounts of electricity isn’t going to win hearts and minds of the neighborhood. Undersea real estate make sense there too.

Passive cooling is wonderful, and really drops the energy footprint of a data center, albeit a very small one which is being tested. Scaled up, I can think of another big impact: property taxes. Does anyone know what the law says about dropping a pod in the ocean? As far as I can tell, laying undersea cabling is expensive, but once installed there are no landlords holding out their hands for a monthly extraction. Rent aside, taking up space with windowless buildings sucking huge amounts of electricity isn’t going to win hearts and minds of the neighborhood. Undersea real estate make sense there too.