There’s something about lawn mowers and hackers. A desire to make them into smart, independent robots. Probably in preparation for the day when Skynet becomes self-aware or the Borg collective comes along to assimilate them into the hive. [Ostafichuk] wanted his to be ready when that happens, so he’s building a Raspberry-Pi powered, Dalek costumed Lawn Mower that is still a work in progress since starting on it in 2014. According to him, “commercial robot lawn mowers are too expensive and not nearly terrifying enough to be any fun, so I guess I will just have to build something myself…”

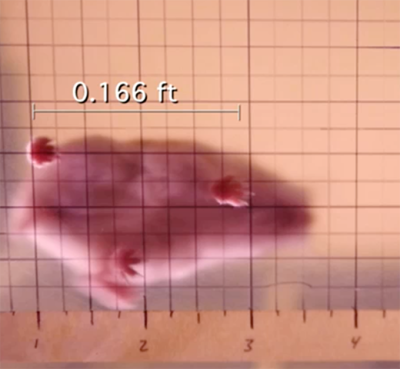

His first report describes the basic skeletal structure he built using scrap pieces of wood. Two large lawn tractor wheels and a third pivot wheel help with locomotion. The two large wheels are driven by geared motors originally meant for car seat height adjustments. A deep cycle 12V battery, and solar panels for charging would take care of power. A raspberry-pi provides the brain power for the Dalek-Mower and L298N based drivers help drive the motors. The body was built from some more planks of scrap wood that he had lying around. While waiting around for several parts to arrive – ultrasonic sensors, accelerometer, 5V power supply modules – he started to paint and decorate the wood work. Generous amounts of water repellent paint and duct tape were used to make it weather proof. His initial plan was to use python for the code, but he later switched to programming in c along with wiringPi library. Code for the project is available from his bitbucket git repository. Load testing revealed that the L298N drivers were not suitable for the high current drawn by the motors, so he changed over to relays to drive them.