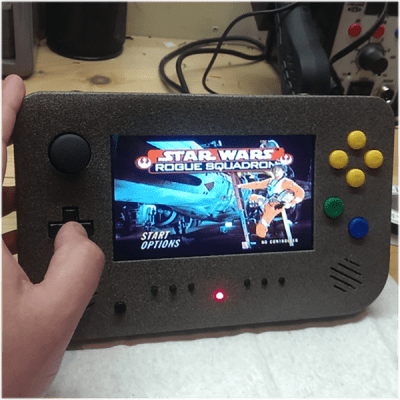

With dozens of powerful single board Linux computers available, you would think the time-tested practice of turning vintage video game consoles would be a lost art. Emulators are available for everything, and these tiny Linux boxes are smaller than the original circuitry found in these old consoles. [Chris], one of the best console modders out there, is still pumping out projects. His latest is a portable N64, and it’s exactly what we’ve come to expect from one of the trade’s masters.

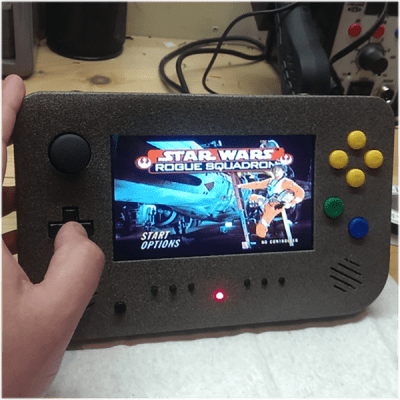

We’ve seen dozens of Nintendo 64s modded into battery-powered handhelds over the years, and [Chris]’ latest project follows the familiar format: remove the PCB from the console, add a screen, some buttons, and a battery, and wrap everything up in a nice case. It’s the last part of the build – the case – that is interesting here. The case was fabricated using a combination of 3D printing CNC machining.

The enclosure for this project was initially printed in PLA, the parts glued together and finally filled for a nice, smooth finish. [Chris] says PLA was a bad choice – the low melting point means the heat from milling the face plate gums up the piece. In the future, he’ll still be using printed parts for enclosures, but for precision work he’ll move over to milling polystyrene sheets.

The enclosure for this project was initially printed in PLA, the parts glued together and finally filled for a nice, smooth finish. [Chris] says PLA was a bad choice – the low melting point means the heat from milling the face plate gums up the piece. In the future, he’ll still be using printed parts for enclosures, but for precision work he’ll move over to milling polystyrene sheets.

With the case completed, a few heat sinks were added to the biggest chips on the board, new button breakout board milled, and a custom audio amp laid out. The result is a beautifully crafted portable N64 that is far classier and more substantial than any emulator could ever pull off.

[Chris] put together a video walkthrough of his build. You can check that out below.

Continue reading “A Beautifully Crafted N64 Portable” →

The enclosure for this project was initially printed in PLA, the parts glued together and finally filled for a nice, smooth finish. [Chris] says PLA was a bad choice – the low melting point means the heat from milling the face plate gums up the piece. In the future, he’ll still be using printed parts for enclosures, but for precision work he’ll move over to milling polystyrene sheets.

The enclosure for this project was initially printed in PLA, the parts glued together and finally filled for a nice, smooth finish. [Chris] says PLA was a bad choice – the low melting point means the heat from milling the face plate gums up the piece. In the future, he’ll still be using printed parts for enclosures, but for precision work he’ll move over to milling polystyrene sheets.