This week and next we take off for the holidays! We have an exciting schedule after the break, so stay tuned!

Continue reading “FLOSS Weekly Episode 813a: Happy Holidays!”

This week and next we take off for the holidays! We have an exciting schedule after the break, so stay tuned!

Continue reading “FLOSS Weekly Episode 813a: Happy Holidays!”

A common theme in modern consumer electronics is having a power button that can be tapped to turn the device on, but needs to be held down when it’s time to shut it off. [R. Jayapal] had noticed a circuit design for this setup when using DC and decided to create a version that could handle AC-powered loads.

The circuit relies on a classic optoisolated triac to switch the AC line, although [R. Jayapal] notes that a relay would also work. The switch circuit consists of two transistors, a comparator, a flip flop and a monostable. As you might expect, the button triggers the flip flops to turn the triac on. However, if you hold the switch for more than a few seconds, a capacitor charges and causes the comparator to trip the output flip flop.

The DC circuit that inspired this one is naturally a bit simpler, although we might have been tempted to simply use the output of that circuit to drive a relay or triac. On the other hand, the circuit is set up to allow you to adjust the time delay easily.

Given the collection of parts, though, we wonder if you couldn’t press some 555s into service for this to further reduce the part count. If relays are too old-fashioned for you, you can always use a solid-state relay or make your own.

2020 saw the world rocked by widespread turmoil, as a virulent new pathogen started claiming lives around the globe. The COVID-19 pandemic saw a rush on masks, air filtration systems, and hand sanitizer, as terrified populations sought to stave off the deadly virus by any means possible.

Despite the fresh attention given to indoor air quality and airborne disease transmission, there remains one technology that was largely overlooked. It’s the concept of upper-room UV sterilization—a remarkably simple way of tackling biological nastiness in the air.

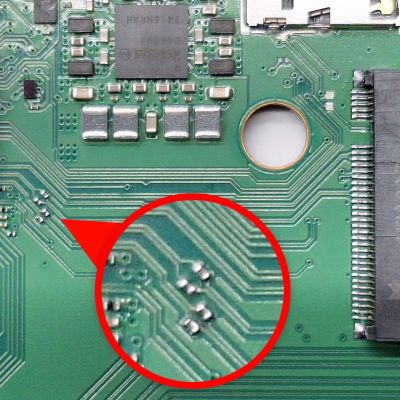

With the recent teardown of the Raspberry Pi 500, there were immediately questions raised about the unpopulated M.2 pad and related traces hiding inside. As it turns out, with the right parts and a steady hand it only takes a bit of work before an NVMe drive can be used with the RP500, as [Jeff Geerling] obtained proof of. This contrasts with [Jeff]’s own attempt involving the soldering on of an M.2 slot, which saw the NVMe drive not getting any power.

The missing ingredients turned out to be four PCIe coupling capacitors on the top of the board, as well as a source of 3.3 V. In a pinch you can make it work with a bench power supply connected to the pads on the bottom, but using the bottom pads for the intended circuitry would be much neater.

This is what [Samuel Hedrick] pulled off with the same AP3441SHE-7B as is used on the Compute Module 5 IO board. The required BOM for this section which he provides is nothing excessive either, effectively just this one IC and required external parts to make it produce 3.3V.

With the added cost to the BOM being quite minimal, this raises many questions about why this feature (and the PoE+ feature) were left unpopulated on the PCB.

Featured image: The added 3.3 V rail on the Raspberry Pi 500 PCB. (Credit: Samuel Hedrick)

These days, very few of us use optical media on the regular. If we do, it’s generally with a slot-loading console or car stereo, or an old-school tray-loader in a desktop or laptop. This has been the dominant way of using consumer optical media for some time.

Step back to the early CD-ROM era, though, and things were a little kookier. Back in the late 1980s and early 1990s, drives hit the market that required the use of a bulky plastic caddy to load discs. The question is—why did we apparently need caddies then, and why don’t we use them any longer?

The Compact Disc, as developed by Phillips and Sony, was first released in 1982. It quickly became a popular format for music, offering far higher fidelity than existing analog formats like vinyl and cassettes. The CD-ROM followed in 1985, offering hundreds of megabytes of storage in an era when most hard drives barely broke 30 MB. The discs used lasers to read patterns of pits and lands from a reflective aluminum surface, encased in tough polycarbonate plastic. Crucially, the discs featured robust error correction techniques so that small scratches, dust, or blemishes wouldn’t stop a disc from working.

Notably, the first audio CD player—the Sony CDP-101—was a simple tray-loading machine. Phillips’ first effort, the CD100, was a top-loader. Neither used a caddy. Nor did the first CD-ROM drives—the Phillips CM100 was not dissimilar from the CD100, and tray loaders were readily available too, like the Amdek Laserdrive-1. Continue reading “Why Did Early CD-ROM Drives Rely On Awkward Plastic Caddies?”

Does “Pix or it didn’t happen” apply to traveling to the edge of space on a balloon-lofted solar observatory? Yes, it absolutely does.

The breathtaking views on this page come courtesy of IRIS-2, a compact imaging package that creators [Ramón García], [Miguel Angel Gomez], [David Mayo], and [Aitor Conde] recently decided to release as open source hardware. It rode to the edge of space aboard Sunrise III, a balloon-borne solar observatory designed to study solar magnetic fields and atmospheric plasma flows.

The itch to investigate lurks within all us hackers. Sometimes, you just have to pull something apart to learn how it works. [Stephen Crosby] found himself doing just that when he got his hands on a Flume water monitor.

[Stephen] came by the monitor thanks to a city rebate, which lowered the cost of the Flume device. It consists of two main components: a sensor which is strapped to the water meter, and a separate “bridge” device that receives information from the sensor and delivers it to Flume servers via WiFi. There’s a useful API for customers, and it’s even able to integrate with a Home Assistant plugin. [Stephen] hoped to learn more about the device so he could scrape raw data himself, without having to rely on Flume’s servers.

Through his reverse engineering efforts, [Stephen] was able to glean how the system worked. He guides us through the basic components of the battery-powered magnetometer sensor, which senses the motion of metering components in the water meter. He also explains how it communicates with a packet radio module to the main “bridge” device, and elucidates how he came to decompile the bridge’s software.

When he sent this one in, [Stephen] mentioned the considerable effort that went into reverse engineering the system was “a very poor use” of his time — but we’d beg to differ. In our book, taking on a new project is always worthwhile if you learned something along the way. Meanwhile, if you’ve been pulling apart some weird esoteric commercial device, don’t hesitate to let us know what you found!