When it comes to IoT and robotics, the name of the game is sensors. These aren’t just IMUs and the stuff that makes robots move — we’re talking about environmental sensors here. Everything from sensors that measure temperature, air quality, humidity, chemical sensors, and radiation sensors are on the table here. For this week’s Hack Chat, we’re talking all about environmental sensors with a hardware designer who has put them to the test.

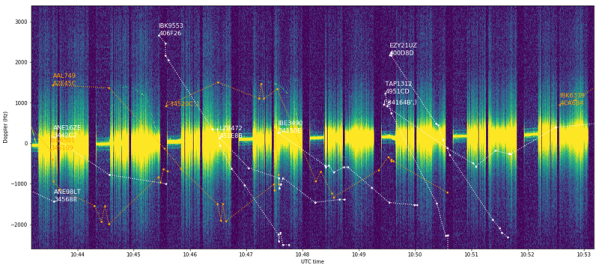

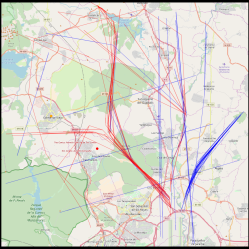

Our guest for this week’s Hack Chat is Radu Motisan. He was a finalist in the 2014 Hackaday Prize with the uRad Monitor, a self-contained radiation monitoring network that sends radiation measurements out to a central server, that can be viewed by the entire world. The goal of this project is to create a worldwide network of radiation monitoring devices, and we’re going to say Radu has succeeded. There are hundreds of these uRad Monitors in over forty countries, and all of them are churning out data about the radiation environment in their neck of the woods.

Our guest for this week’s Hack Chat is Radu Motisan. He was a finalist in the 2014 Hackaday Prize with the uRad Monitor, a self-contained radiation monitoring network that sends radiation measurements out to a central server, that can be viewed by the entire world. The goal of this project is to create a worldwide network of radiation monitoring devices, and we’re going to say Radu has succeeded. There are hundreds of these uRad Monitors in over forty countries, and all of them are churning out data about the radiation environment in their neck of the woods.

By training, Radu is a software engineer with a masters in science. In his spare time, Radu plays around with chemistry, physics, and electronics. It’s this background that led Radu to create one of the most amazing Hackaday Prize projects ever.

We’ll kick off with a discussion of Radu’s uRad Monitor, and that means we’ll be covering:

- Radiation Detection, why is it important, and what does it mean?

- How do you detect radiation?

- The differences between Geiger-Mueller tubes and scintillators

You are, of course, encouraged to add your own questions to the discussion. You can do that by leaving a comment on the Environmental Sensor Hack Chat Event Page and we’ll put that in the queue for the Hack Chat discussion.

Our Hack Chats are live community events on the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week is just like any other, and we’ll be gathering ’round our video terminals at noon, Pacific, on Friday, September 7th. Need a countdown timer? We should look into hosting these countdown timers on hackaday.io, actually.

Click that speech bubble to the right, and you’ll be taken directly to the Hack Chat group on Hackaday.io.

You don’t have to wait until Friday; join whenever you want and you can see what the community is talking about.