No spooky mansion is complete without a secret passage accessed through a book shelf — or so Hollywood has taught us. What works as a cliché in movies works equally well in an escape room, and whenever there’s escape rooms paired with technology, [Alastair Aitchison] isn’t far. His latest creation: you guessed it, is a secret bookcase door.

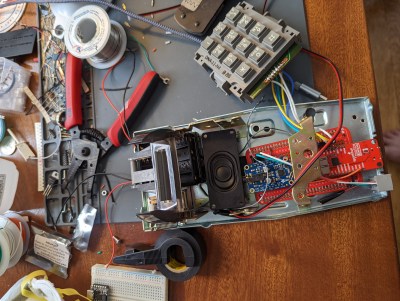

For this tutorial, he took a regular book shelf and mounted it onto a wooden door, with the door itself functioning as the shelf’s back panel, and using the door hinges as primary moving mechanism. Knowing how heavy it would become once it’s filled with books, he added some caster wheels hidden in the bottom as support. As for the (un)locking mechanism, [Alastair] did consider a mechanical lock attached on the door’s back side, pulled by a wire attached to a book. But with safety as one of his main concerns, he wanted to keep the risk of anyone getting locked in without an emergency exit at a minimum. A fail-safe magnetic lock hooked up to an Arduino, along with a kill switch served as solution instead.

Since his main target is an escape room, using an Arduino allows also for a whole lot more variety of integrating the secret door into its puzzles, as well as ways to actually unlock it. How about by solving a Rubik’s Cube or with the right touch on a plasma globe?