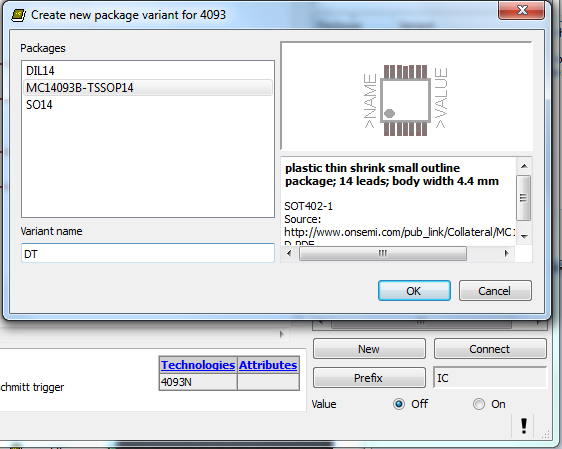

We would wager that by weight this project is mostly wiring. We might go as far as betting that the wire outweighs the rest of the components 2 to 1. We’ll keep our fingers crossed that there’s never a loose connection, but for now it seems that [Kevin Horton’s] NAND-based computer project is up and running. Very nearly ever part of the build is based on NAND gates, which is why the point-to-point wiring is so crazy. There is one peripheral board which uses some non-NAND components, but he eventually plans on replacing that to make the system…. pure?

Now get ready for the crazy part. This is just one half of the program counter! There’s another board that looks just like it. The two join at least a half-dozen other boards of similar size and complexity to make a functioning computer. Crazy! The post shares a ton of details, but you can also just skip down after the break to see a video of it running a program.

If you’re wondering how a NAND-based computer works you should make your way through this online course.