A while back we got an anonymous complaint that Hackaday was “elitist”, and that got me thinking. We do write up the hacks that we find the coolest, and that could lead to a preponderance of gonzo projects, or a feeling that something “isn’t good enough for Hackaday”. But I really want to push back against that notion, because I believe it’s just plain wrong.

One of the most important jobs of a Hackaday writer is to find the best parts of a project and bring that to the fore, and I’d like to show you what I mean by example. Take this post from two weeks ago that was nominally about rescuing a broken beloved keyboard by replacing its brain with a modern microcontroller. On its surface, this should be easy – figure out the matrix pinout and wire it up. Flash in a keyboard firmware and you’re done.

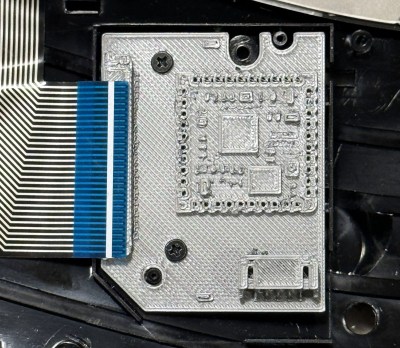

Of course we all love a good hardware-rescue story, and other owners of busted Sculpt keyboards will be happy to see it. But there’s something here for the rest of us too! To figure out the keyboard matrix, it would take a lot of probing at a flat-flex cable, so [TechBeret] made a sweet breakout board that pulled all the signals off of the flat-flex and terminated them in nicely labelled wires. Let this be your reminder that making a test rig / jig can make these kind of complicated problems simpler.

Once the pinout was figured out, and a working prototype made, it was time to order a neat PCB and box it up. The other great trick was the use of 3D-printed mockups of the PCBs to make sure that they fit inside the case, the holes were all in the right places, and that the flat-flex lay flat. With how easily PCB design software will spit out a 3D model these days, you absolutely should take the ten minutes to verify the physical layout of each revision before sending out your Gerbers.

So was this a 1337 hack? Maybe not. But was it worth reading for these two sweet tidbits, regardless of whether you’re doing a keyboard hack? Absolutely! And that’s exactly the kind of opportunity that elitists shut themselves off from, and it’s the negative aspect of elitism what we try to fight against here at Hackaday.