Whatever you’re doing with your hand tools, by the US Army’s lights, you’re probably doing it wrong. That seems to be the “Green Machine’s” attitude on pliers and screwdrivers, at least, the main stars of this 1943 War Department training film on the horrors of tool abuse.

As kitschy as the film might be, they weren’t wrong. That’s especially true about the dreaded slip-joint pliers, which seem to find their way onto everyone’s list of unloved tools and are shown being used for their true purpose — turning nuts and bolt heads from hexagons into circles. Once that gore is wrapped up, we’re treated to the proper uses of pliers, including the fascinating Bernard-style parallel jaw pliers. We can recall these beauties kicking around the bottom of Dad’s tool kit and being entranced by the mechanism used to keep the jaws parallel and amplify the force applied. Sadly, those pliers are long gone now; Tubalcain did a great review of these pliers a few years back if you need a refresher.

A selection of screwdrivers gets the same treatment, complete with dire warnings against using them as prybars and chisels. Also against the Army Way is using the wrong size screwdriver for the job, lest you strip the head of the screw or break the tool itself. It has to be said that the Plomb Tool Company of Los Angeles, which produced the film, made some fantastic-looking screwdrivers back in the day. The square shanks on some of those straight screwdrivers are enormous, and the wooden handles look so much more comfortable than the greebled-up plastic nonsense manufacturers seem to favor these days. Also interesting is the reference to the new-fangled Phillips screw, not to mention the appearance of a Yankee-style spiral ratcheting screwdriver, another of Dad’s prized acquisitions that thankfully is still around to this day.

What strikes us about these military training films is how many of them were produced. No subject seemed too mundane to get a training film made about it, and so many were made that one is left wondering how there was any time left for soldiering after watching all these films. But really, it’s not much different today, when we routinely pull up a random YouTube video to get a quick visual demo of how to do something we’ve never tried before. The medium may have changed, but visual learning is still a thing.

Continue reading “Retrotechtacular: How Not To Use Hand Tools” →

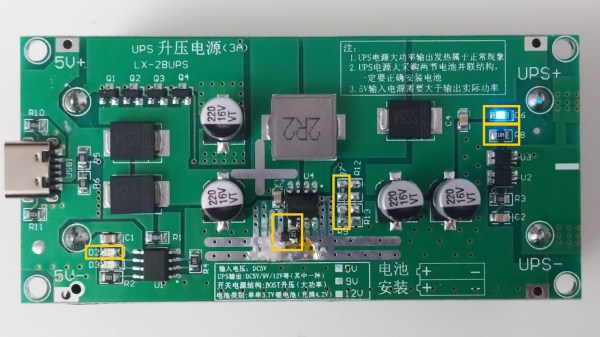

![The patched up XR2981 boost IC with MCP809 reset IC installed. (Credit: [MisterHW])](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/upload_34f9a5c70d7738a67185359c3110505b.jpg?w=400)