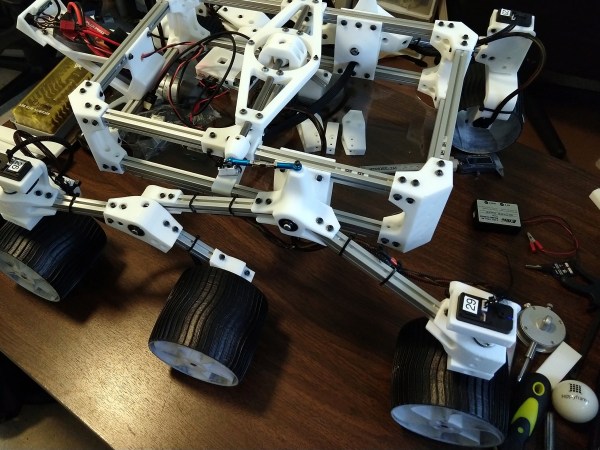

For his Hackaday prize entry, [Daren Schwenke] is creating an open-source pick-and-place head for a 3D printer which, is itself, mostly 3D printable. Some serious elbow grease has gone into the design of this, and it shows.

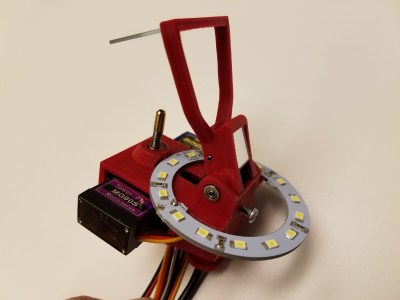

The really neat part of this project comes in the imaging of the part being placed. The aim is to image the part whilst it’s being moved, using a series of mirrors which swing out beneath the head. A Raspberry Pi camera is used to grab the photos, an LED halo provides consistent lighting, and whilst it looks like OpenPnP may have to be modified slightly to make this work, it will certainly be impressive to see.

Two 9g hobby servos are used: one to swing out the mirrors (taking 0.19 seconds) and one to rotate the part to the correct orientation (geared 2:1 to allow 360 degrees part rotation). Altogether the head weighs 59 grams – lighter than an E3D v6.

In order to bring this project to its current state, [Daren] has had to perform some auxiliary hacks. The first was an aquarium to vacuum pump conversion – by switching around the valves and performing some other minor mods, [Daren] was able to produce a vacuum of 231mbar. The second was hacking a two-way solenoid valve from a coffee machine into a three-way unit. As [Daren] says, three-way valves are not expensive, but “a part in hand is worth two on Alibaba.”

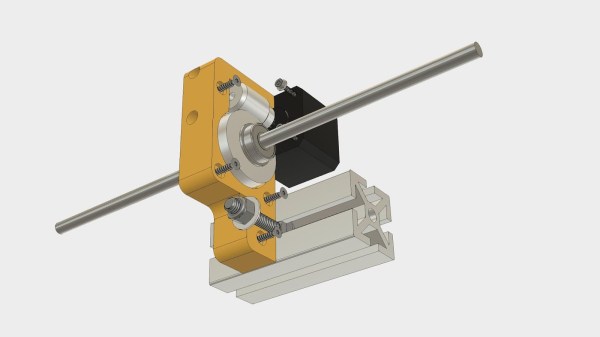

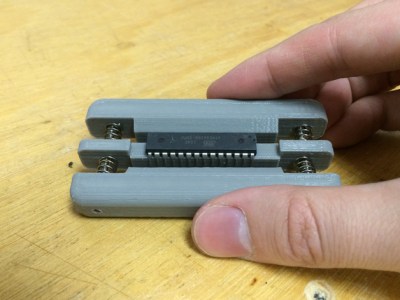

Fresh from the factory Dual Inline Package (DIP) chips come with their legs splayed every so slightly apart — enough to not fit into the carefully designed footprints on a circuit board. You may be used to imprecisely bending them by hand on the surface of the bench. [Marco] is more refined and shows off a neat little spring loaded tool that just takes a couple of squeezes to neatly bend both sides of the DIP, leaving every leg the perfect angle. Shown here is

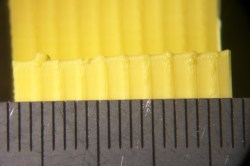

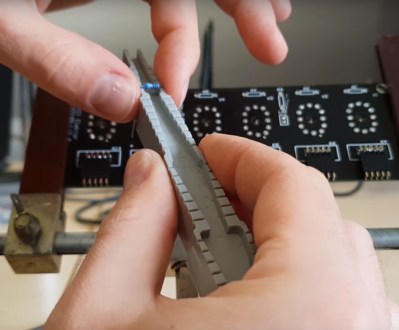

Fresh from the factory Dual Inline Package (DIP) chips come with their legs splayed every so slightly apart — enough to not fit into the carefully designed footprints on a circuit board. You may be used to imprecisely bending them by hand on the surface of the bench. [Marco] is more refined and shows off a neat little spring loaded tool that just takes a couple of squeezes to neatly bend both sides of the DIP, leaving every leg the perfect angle. Shown here is  Another tool which caught our eye is the one he uses for bending the metal film resistor leads: the “Biegelehre” or lead bending tool. You can see that [Marco’s] tool has an angled trench to account for different resistor body widths, with stepped edges for standard PCB footprint spacing. We bet you frequently use the same resistor bodies so 3D printing is made easier by

Another tool which caught our eye is the one he uses for bending the metal film resistor leads: the “Biegelehre” or lead bending tool. You can see that [Marco’s] tool has an angled trench to account for different resistor body widths, with stepped edges for standard PCB footprint spacing. We bet you frequently use the same resistor bodies so 3D printing is made easier by

Work long enough with 3D printers, and our ideas inevitably grow beyond our print volume. Depending on the nature of the project, it may be possible to divide into pieces then glue them together. But usually a larger project also places higher structural demands ill-suited to plastic.

Work long enough with 3D printers, and our ideas inevitably grow beyond our print volume. Depending on the nature of the project, it may be possible to divide into pieces then glue them together. But usually a larger project also places higher structural demands ill-suited to plastic.