Shredding things isn’t just good for efficiently and securely disposing of them. It’s also very fun, as well. [Joonas] of [Let’s Print] didn’t have a shredder, so set about 3D printing one of their very own.

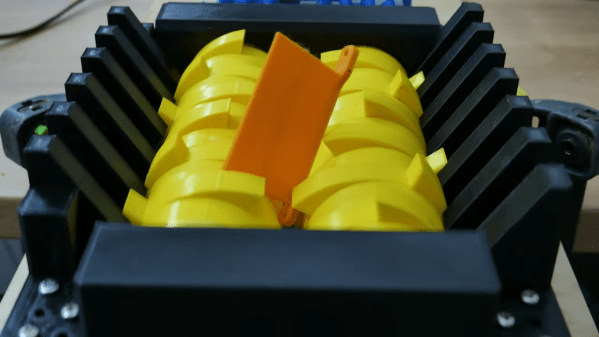

The design apes that of the big metal trash shredders you’ve probably seen in videos all over the internet. They use a pair of counter-rotating drums with big teeth. As the drums turn, the teeth grab and pull objects into the gap between the drums, where they are duly torn apart into smaller pieces.

In this design, plastic drums are pressed into service as [Joonas] does not have a metal 3D printer. A brushed DC motor is used to drive the shredder. A large multi-stage gearbox is used to step down the motor’s output and provide plenty of torque to do the job.

The shredder gets tested with plenty of amusing garbage. Everything from old vegetables, to paper, and rock-hard old cheeseburgers are put through the machine. It does an able job in all cases, though obviously the plastic drums can’t handle the same kind of jobs as a proper metal shredder. Harder plastics and aluminium cans stall out the shredder, though. The gearbox also tends to strip gears on the tougher stuff. The basic theory is sound, but some upgrades could really make this thing shine.

Is it a device that will see a lot of practical use? Perhaps not. Is it a fun device that would be the star of your next hackerspace Show and Tell? Absolutely. Plus it might be a great way to get rid of lots of those unfinished projects that always clog up your storage areas, too! Video after the break.

Continue reading “3D-Printed Shredder Eats Lettuce For Breakfast”