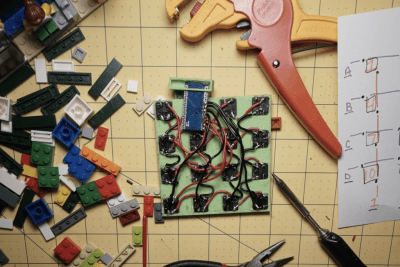

Like so many of us, [EducatedAce] has been quelling the quarantine blues by resurrecting old projects and finding new challenges to fill the days. He’s just finished building this blocky macro keypad to hold a bunch of shortcuts for Photoshop, thus continuing and compounding the creative spree.

[EducatedAce] already had everything on hand except the Arduino Micro. Instead of standard key switches, this macro block uses 16 of the loudest, crunchiest tactile buttons out there — those big ones with the yellow stems that sound like small staplers.

[EducatedAce] already had everything on hand except the Arduino Micro. Instead of standard key switches, this macro block uses 16 of the loudest, crunchiest tactile buttons out there — those big ones with the yellow stems that sound like small staplers.

And don’t worry — no LEGO or LEGO accessories were harmed in the making of this macro pad — the base plate and switch plate are 3D printed. [EducatedAce] has the STL files posted along with great build instructions if you want to wire one up for yourself.

This is a great project because it’s sturdy, it gets the job done without a lot of expense, and still looks like something you’d want on your desk. [EducatedAce] plans to rebuild it with uniformly colored bricks, but we think it looks great as-is, especially with those vented 1×2 pieces. If it were ours, we might use a different color for each row or column to help keep the shortcuts straight.

What? You’ve never printed your own interlocking building blocks before? Well, don’t limit yourself to 1:1 scale, otherwise the minifigs have won. Build a go-kart big enough for humans!