[JAC_101], the Director of Legal Evil Emeritus for LVL1 Hackerspace (don’t ask me, it’s their title system), was challenged to a hacking duel. It all started years ago. The person who is now president of LVL1, visited the space for the first time and brought with her a discarded Apple II controller for Lego bricks which had previously belonged to her father. Excited to test it, the space found that, unfortunately, LVL1’s Apple II wouldn’t boot. An argument ensued, probably some trash talking, and [JAC_101] left with the challenge: Could he build an Arduino interface for the Apple II Lego controller quicker than the hackerspace could fix its Apple II?”

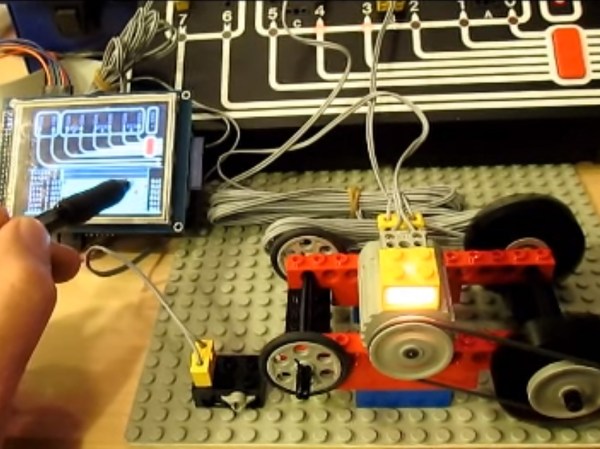

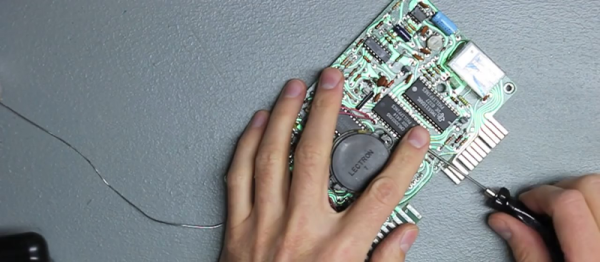

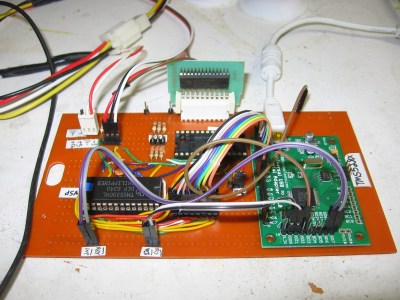

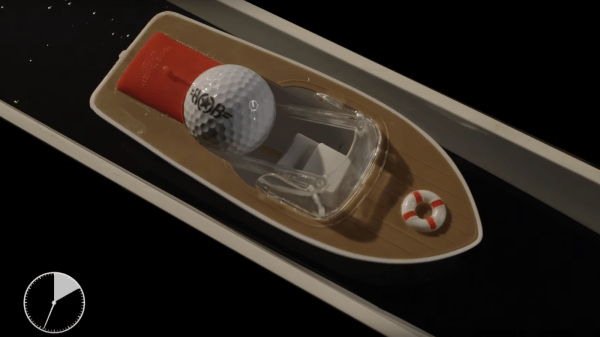

In the end, a concentrated force by one hacker over two years overcame the collective ADHD of many. He began by opening the interface to look inside, a completely unnecessary step since he found it was already thoroughly documented. Next he forgot about the project for a year. Then he remembered it, and built an interface for an Arduino Uno to hook to the controller and wrote a library for the interface. Realizing that sending serial commands was not in line with the original friendly intention of the device, he added a graphical display to the project; which allowed the user to control the panel with touch. In the end he won the challenge and LVL1 still doesn’t have a working Apple II. We assume some gloating occurred. Some videos of it in action after the break.

Continue reading “Lego Technic Of The Past Eliminates Apple ][ With Arduino And Touchscreen”