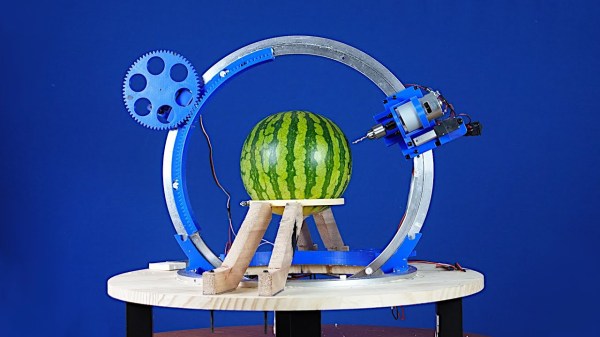

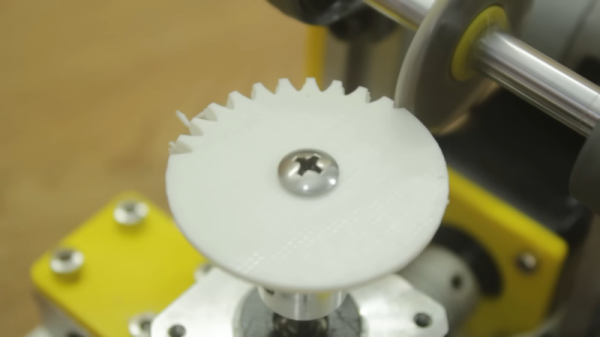

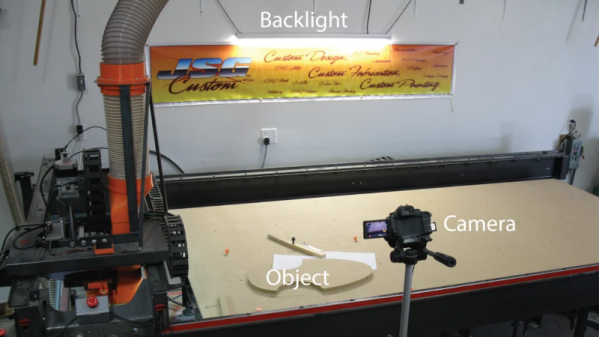

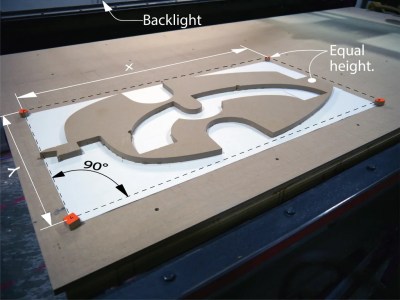

It is the time of year when a lot of people in certain parts of the world carve pumpkins. [Gonkee] is carving a watermelon, which we assume is similar. He decided to make a CNC machine to do the carving for him. The unusual part is the use of two lazy Susans to make a rotary carving machine. You can see the result in the video below.

The hardware is clever and there is software that lets you do drawings, although we were hoping for something that would process gcode or slice STL. That would be a worthy add-on project. There were a few iterations required before the Melon Carver 3000 worked satisfactorily. Seeing a carving tool operating on two circles gives us a lot of ideas. We aren’t sure how sturdy the mounts are, so don’t plan on carving aluminum without some changes, but we suspect it is possible.

Then again, a laser head mounted on the frame would have probably made short work of the melon, and wouldn’t require much mechanical stiffness. It would, however, take a little effort to keep it in focus. So many ideas to try!

Watermelon is a popular hacking medium, apparently. There’s even one that holds a GameBoy.