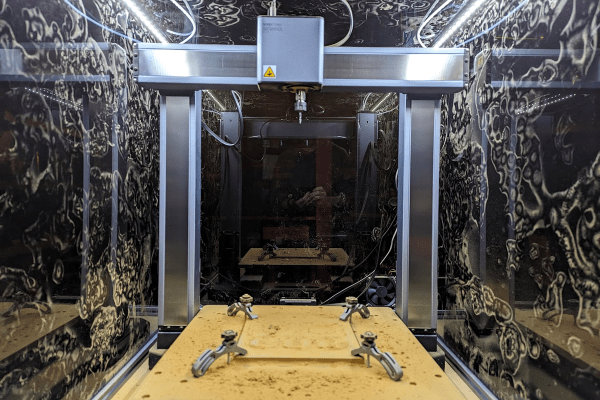

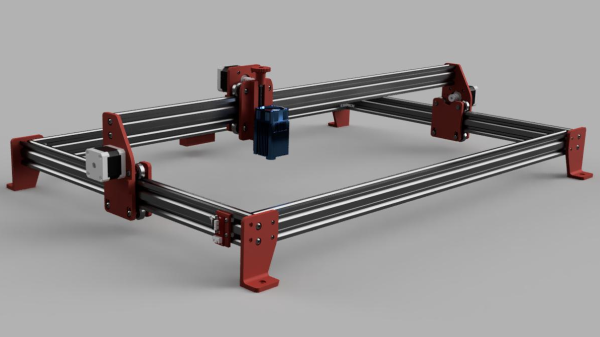

As anyone who has used an FDM printer can tell you, it’s certainly not the magical replicator it’s often made out to be. The limitations of the platform are numerous — ranging from anisotropic material characteristics to visual imperfections in the parts. In an attempt to reduce the visual artifacts in 3D prints, [TenTech] affixed a small diode laser on a 3D printer.

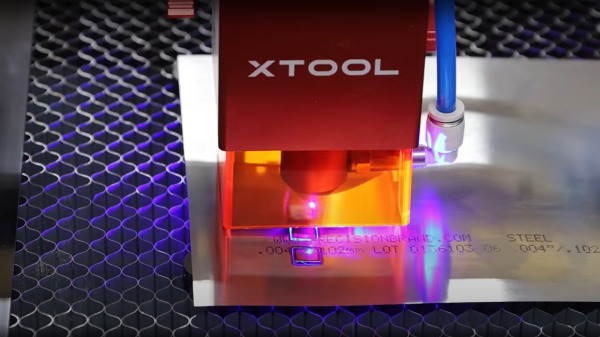

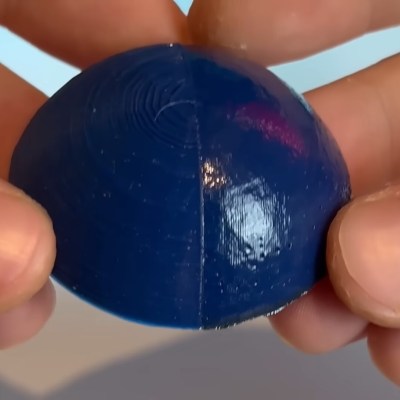

Getting the 1.5 watt diode laser onto the printer was a simple matter of a bracket and attaching it to the control board as a fan. Tuning the actual application of the laser proved a little more challenging. While the layer lines did get smoothed, it also discolored the pink filament making the results somewhat unusable. Darker colored filaments seem to not have this issue and a dark blue is used for the rest of the video.

The smoothing process begins at the end of a 3D print and uses non-planar printer movements to keep the laser at an ideal focusing distance. The results proved rather effective, giving a noticeably smoother and shiner quality than an unprocessed print. The smoothing works incredibly well on fine geometry which would be difficult or impossible to smooth out via traditional mechanical means. Some detail was lost with sharp corners getting rounded, but not nearly as much as [TenTech] feared.

The smoothing process begins at the end of a 3D print and uses non-planar printer movements to keep the laser at an ideal focusing distance. The results proved rather effective, giving a noticeably smoother and shiner quality than an unprocessed print. The smoothing works incredibly well on fine geometry which would be difficult or impossible to smooth out via traditional mechanical means. Some detail was lost with sharp corners getting rounded, but not nearly as much as [TenTech] feared.

For a final test, [TenTech] made two candle molds, one smoothed and one processed. The quality difference between the two resulting candles was minimal, with the smoothed one being perhaps even a little worse. However, a large amount of wax leaked into the 3D print infill in the unprocessed mold, with the processed mold showing no signs of leaking.

If you are looking for a bit safer of a 3D print post-processing technique, make sure to check out [Donal Papp]’s UV resin smoothing experiments!