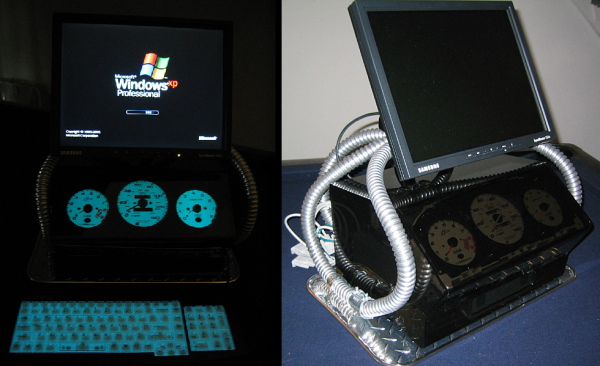

The last thing you’d expect to see adorned on a computer case is an Indiglo gauge cluster straight out of a Honda Civic…. but that is exactly what [Envador] has created. He was driving around town one evening when a car past him. The blue glow of the passing car’s dash board was extremely noticeable and caught his attention in a positive way. Any computer nerd would, of course, immediately think “hey, that would make a cool computer case“. [Envador] then set out on a mission to make it happen.

Clearly, the focus of the case is the gauge cluster. It was taken out of a Honda Civic found in a junkyard. And it just wouldn’t be cool enough to just have the gauges light up, they definitely had to display some sort of info from the computer. CPU, RAM and hard drive usage seemed like pretty good parameters to display. [Envador] expected that each of the 3 gauges would accept a pulsed signal to move the needle. After tearing down the gauge panel he found only the tachometer worked that way. The other two gauges worked by some unknown means. Instead of messing around with figuring those two out, the mechanical components of the rogue gauges were replaced with those of two aftermarket tachometers. The stock needles and indiglo backlighting were kept.

To move the now-3 tachometer needles, [Envador] used a product called PCTach that connects to the PC via serial cable. It works with accompanying software to monitor PC information and output the necessary signals to make the tachometers move according to the PC’s performance. The computer case, itself, was fabricated from smoked acrylic behind which sits the gauge cluster. A matching backlit keyboard finishes off the look nicely.