[Prof. Marvin Minsky] is a very well-known figure in the field of computing, having co-founded the MIT AI lab, published extensively on AI and computational intelligence, and, let’s not forget, inventing the confocal microscope and, of course, the useless machine. But did you know he also was a co-developer of the first Logo “turtle,” and developed a computer intended to run Logo applications in an educational environment? After dredging some PDP-10 tapes owned by the MIT Media Lab, the original schematics for his machine, the Turtle Terminal TT2500 (a reference to the target price of $2500, in 1970 terms), are now available for you to examine.

computer hacks1419 Articles

computer hacks

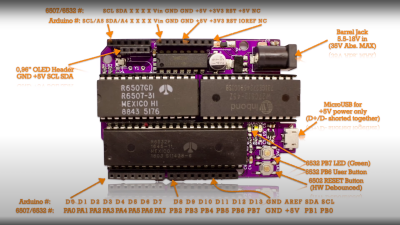

A Simple Guide To Bit Banged I2C On The 6502

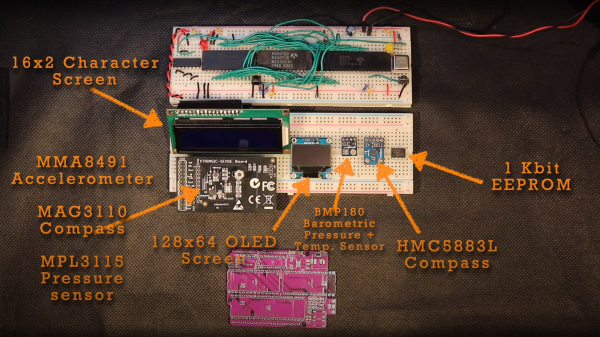

We covered [Anders Nielsen]’s 65duino project a short while ago, and now he’s back with an update video showing some more details of bit-banging I2C using plain old 6502 assembly language.

Obviously, with such a simple system, there is no dedicated I2C interface hardware, so the programmer must take care of all the details of the I2C protocol in software, bit-banging it out to the peripheral and reading back the response one bit at a time.

The first detail to concern us will be the I2C addresses of the devices being connected to the bus and how low-level bit manipulation is used to turn the 7-bit I2C address into the byte being bit-banged. As [Anders] shows , setting a bit is simply a logical-OR operation, and resetting a bit is a simple logical-AND operation using the inversion (or one’s complement) bit to reset to form a bitmask. As many will already know, this process is necessary to code for a read or a write I2C operation. A further detail is that I2C uses an open-collector connection scheme, which means that no device on the bus may drive the bus to logical high; instead, they must release the drive by going to the high impedance state, and an external pull-up resistor will pull the bus high. The 6532 RIOT chip (used for I/O on the 65unio) does not have tristate control but instead uses a data direction register (DDR) to allow a pin to be an input. This will do the job just fine, albeit with slightly odd-looking code, until you know what’s going on.

, setting a bit is simply a logical-OR operation, and resetting a bit is a simple logical-AND operation using the inversion (or one’s complement) bit to reset to form a bitmask. As many will already know, this process is necessary to code for a read or a write I2C operation. A further detail is that I2C uses an open-collector connection scheme, which means that no device on the bus may drive the bus to logical high; instead, they must release the drive by going to the high impedance state, and an external pull-up resistor will pull the bus high. The 6532 RIOT chip (used for I/O on the 65unio) does not have tristate control but instead uses a data direction register (DDR) to allow a pin to be an input. This will do the job just fine, albeit with slightly odd-looking code, until you know what’s going on.

From there, it’s a straightforward matter to write subroutines that generate the I2C start, stop, and NACK conditions that are required to write to the SSD1306-based OLED to get it to do something we can observe. From these basic roots, through higher-level subroutines, a complete OLED library in assembly can be constructed. We shall sit tight and await where [Anders] goes next with this!

We see I2C-connected things all the time, like this neat ATtiny85-based I2C peripheral, and whilst we’re talking about the SSD1306 OLED display controller, here’s a hack that shows just how much you can push your luck with the I2C spec and get some crazy frame rates.

Continue reading “A Simple Guide To Bit Banged I2C On The 6502”

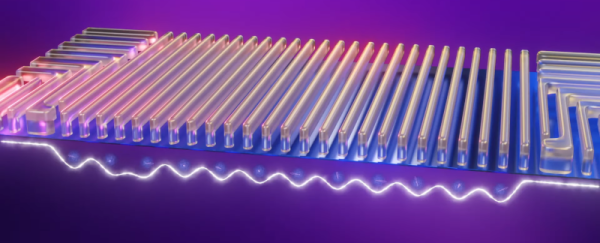

Intel To Ship Quantum Chip

In a world of 32-bit and 64-bit processors, it might surprise you to learn that Intel is releasing a 12-bit chip. Oh, wait, we mean 12-qubit. That makes more sense. Code named Tunnel Falls, the chip uses tiny silicon spin quantum bits, which Intel says are more advantageous than other schemes for encoding qubits. There’s a video about the device below.

It is a “research chip” and will be available to universities that might not be able to produce their own hardware. You probably aren’t going to find them listed on your favorite online reseller. Besides, the chip isn’t going to be usable on a breadboard. It is still going to take a lot of support to get it running.

Intel claims the silicon qubit technology is a million times smaller than other qubit types. The size is on the order of a device transistor — 50 nanometers square — simplifying things and allowing denser devices. In silicon spin qubits, information resides in the up or down spin of a single electron.

Of course, even Intel isn’t suggesting that 12 qubits are enough for a game-changing quantum computer, but you do have to start somewhere. This chip may enable more researchers to test the technology and will undoubtedly help Intel accelerate its research to the next step.

There is a lot of talk that silicon is the way to go for scalable quantum computing. It makes you wonder if there’s anything silicon can’t do? You can access today’s limited quantum computers in the proverbial cloud.

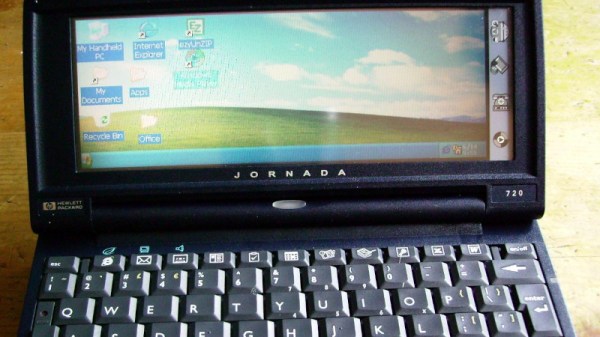

Your IPhone Can’t Do What This WinCE Device Can!

Most of us probably now have a smartphone, an extremely capable pocket computer — even if sometimes its abilities are disguised a little by its manufacturer. There are many contenders to the crown of first smartphone, but in that discussion it’s often forgotten that the first generally available such devices weren’t phones at all, but PDAs, or Personal Digital Assistants. The fancier ones blurred the line between PDA and laptop and were the forerunner devices to netbooks, and it’s one of these that [Remy] is putting through its paces. He makes the bold claim that it can do things the iPhone can’t, and while the two devices are in no way comparable he’s right on one point. His HP Journada 720 can host a development environment, while the iPhone can’t.

The HP was something of a turn-of-the-millennium object of desire, being a palmtop computer with a half-decent keyboard a 640×240 pixel TFT display, and 32 MB of RAM alongside its 206 MHz Intel StrongARM CPU. Its Windows CE OS wasn’t quite the desktop Windows of the day, but it was close enough to be appealing for the ’90s exec who had everything. Astoundingly it has more than one Linux distro that can run on it with some level of modernity, which is where he’s able to make the claim about the iPhone being inferior.

We remember the Journada clamshell series from back in the day, though by our recollection the battery life would plummet if any attempt was made to use the PCMCIA slot. It was only one of several similar platforms offering a mini-laptop experience, and we feel it’s sad that there are so few similar machines today. Perhaps we’ll keep an eye out for one and relive the ’90s ourselves.

A Modular Analogue Computer

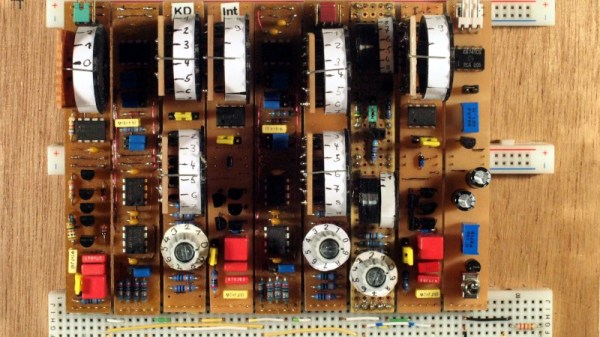

We are all used to modular construction in the analogue synth world, to the extent that there’s an accepted standard for it in EuroRack. But the same techniques are just as useful wherever else analogue circuits need to be configured on the fly, such as in an analogue computer. It’s something [Rainer Glaschick] has pursued, with his Flexible Analog Computer, an analogue computer made from a set of modules mounted on breadboard strips.

Standard modules are an adder and an integrator, with the adder also having inverter, comparator, and precision rectifier functions. The various functions can be easily configured by means of jumpers, and there are digital switches on board to enable or disable outputs and inputs. he’s set up a moon landing example to demonstrate the machine in practice.

We’re not going to pretend to be analogue computer experts here at Hackaday,but we naturally welcome any foray into analogue circuitry lest it become a lost art. If you’d like to experiment with analogue computing there are other projects out there to whet your appetite, and of course they don’t even need to be electronic.

That Handheld 386SX Gets A Teardown

A few weeks ago our community was abuzz with the news of a couple of new portable computers available through AliExpress. Their special feature was that they are brand new 2023-produced retrocomputers, one with an 8088, and the other with a 386SX. Curious to know more? [Yeo Kheng Meng] has one of the 386 machines, and he’s taken it apart for our viewing pleasure.

What he found is a well-designed machine that does exactly what it claims, and which runs Windows 95 from a CF card. It’s slow because it’s an embedded version of the 386 variant with a 16-bit bus originally brought to market as a chip that could work with 16-bit 286-era chipsets. But the designer has done a good job of melding old and new parts to extract the most from this vintage chip, and has included some decidedly modern features unheard of in the 386 era such as a CH375B USB mass storage interface.

If we had this device we’d ditch ’95 and run DOS for speed with Windows 3.1 where needed. Back in the day with eight megabytes of RAM it would have been considered a powerhouse before users had even considered its form factor, so there’s an interesting exercise for someone to get a vintage Linux build running on it.

One way to look at it is as a novelty machine with a rather high price tag, but he makes the point that considering the hardware design work that’s gone into it, the 200+ dollar price isn’t so bad. With luck we’ll get to experience one hands-on in due course, and can make up our own minds. Our original coverage is here.

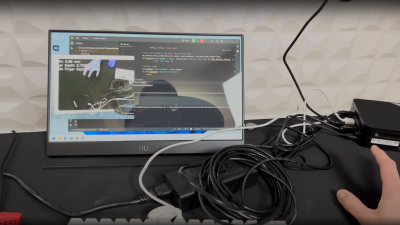

An Almost Invisible Desktop

When you’re putting together a computer workstation, what would you say is the cleanest setup? Wireless mouse and keyboard? Super-discrete cable management? How about no visible keeb, no visible mouse, and no obvious display?

That’s what [Basically Homeless] was going for. Utilizing a Flexispot E7 electronically raisable standing desk, an ASUS laptop, and some other off-the-shelf parts, this project is taking the idea of decluttering to the extreme, with no visible peripherals and no visible wires.

There was clearly a lot of learning and much painful experimentation involved, and the guy kind of glazed over how a keyboard was embedded in the desk surface. By forming a thin layer of resin in-plane with the desk surface, and mounting the keyboard just below, followed by lots of careful fettling of the openings meant the keys could be depressed. By not standing proud of the surface, the keys were practically invisible when painted. After all, you need that tactile feedback, and a projection keeb just isn’t right.

Moving on, never mind an ultralight gaming mouse, how about a zero-gram mouse? Well, this is a bit of a cheat, as they mounted a depth-sensing camera inside a light fitting above the desk, and built a ChatGPT-designed machine-learning model to act as a hand-tracking HID device. Nice idea, but we don’t see the code.

The laptop chassis had its display removed and was embedded into the bottom of the desk, along with the supporting power supplies, a couple of fans, and a projector. To create a ‘floating’ display, a piece of transparent plastic was treated to a coating of Lux labs “ClearBright” transparent display film, which allows the image from the projector to be scattered and observed with sufficient clarity to be usable as a PC display. We have to admit, it looks a bit gimmicky, but playing Minecraft on this setup looks a whole lotta fun.

Many of the floating displays we’ve covered tend to be for clocks (after all timepieces are important) like this sweet HUD hack.