Something odd happened to git.centos.org last week. That’s the repository where Red Hat has traditionally published the source code to everything that’s a part of Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) to fulfill the requirements of the GPL license. Last week, those packages just stopped flowing. Updates weren’t being published. And finally, Red Hat has published a clear answer to why:

Red Hat has decided to continue to use the Customer Portal to share source code with our partners and customers, while treating CentOS Stream as the venue for collaboration with the community.

Sounds innocuous, but what’s really going on here? Let’s have a look at the Red Hat family: RHEL, CentOS, and Fedora.

RHEL is the enterprise Linux distribution that is Red Hat’s bread and butter. Fedora is RHEL’s upstream distribution, where changes happen fast and things occasionally break. CentOS started off as a community repackaging of RHEL, as allowed under the GPL and other Open Source licenses, for people who liked the stability but didn’t need the software support that you’re paying for when you buy RHEL.

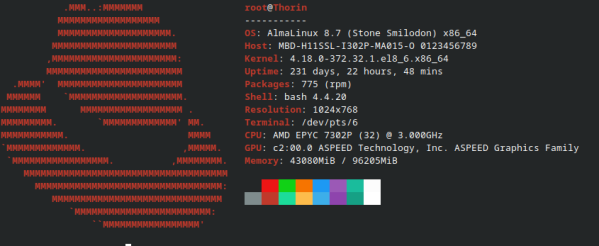

Red Hat took over the reigns of CentOS back in 2014, and then imposed the transition to CentOS Stream in 2020, to some consternation. This placed CentOS Stream between the upstream Fedora, and the downstream RHEL. Some people missed the stability of the old CentOS, and in response a handful of efforts spun up to fill the gap, like Alma Linux and Rocky Linux. These projects took the source from git.centos.org, and rebuilt them into usable community operating systems, staying closer to RHEL in the process.

Red Hat has published a longer statement elaborating on the growth of CentOS Stream, but it ends with an interesting statement: “Red Hat customers and partners can access RHEL sources via the customer and partner portals, in accordance with their subscription agreement.” What exactly is in that subscription agreement? Well according to Alma Linux, “the way we understand it today, Red Hat’s user interface agreements indicate that re-publishing sources acquired through the customer portal would be a violation of those agreements.” Continue reading “Et Tu, Red Hat?”